Will We See Utopia This Side of Heaven?

Is perfection by human means achievable, even across vast timescales?

Hands up those of you who think things on Earth have never been better.

C’mon, don’t be shy. It’s a simple question. Is life better now than it’s ever been? Maybe not your life, necessarily. But life life. Human life—the quality of it, everywhere and anywhere.

No?

You seem reluctant to raise your hand. Maybe it’s because you’re reading this on your phone or computer, and you’re not actually in a lecture hall listening to me ask this question in front of a whole crowd of bashful onlookers, so this whole bit I’m doing is coming across as rather contrived. Fair enough. Maybe you’re holding out because you feel that the totality of human history, spanning all human civilizations, is a bit too broad a timeframe to consider if you intend to give a definitive answer in good faith. Also, fair enough. Or, maybe your hand is staying there, stuck to your side, because you don’t think things are all that great here on this planet of ours. Maybe you think things are downright f***ed, if you’ll pardon my bluntness.

But that’s not exactly what I asked, is it? I didn’t ask if things are good. Just glance at today’s headlines, and you can see for yourself that they definitely aren’t. Instead, I asked if things are better than they have ever been before, at any point in human history.

Okay—one or two of you, edging a sweaty palm upwards. Why the timidity? Not an easy stance to take, is it, given the sheer scale, severity and intractability of the problems we face today. Hunger, disease, war, poverty. They’re all still here with us, just as they’ve always been. It doesn’t seem like we’ve made much progress as a species in overcoming our worst instincts. There’s even an argument to be made that things are much worse than ever before, when you consider just how much destruction we can unleash upon one another. We’ve fought a lot of wars, sure, but at no point in our shared history have we ever had the capability of wiping one another off the face of the Earth. The potential for nuclear holocaust is a very, very real thing. Chew on that, you Rousseau-loving idealists.

But to those few of you who did raise their hands, let’s explore your (tenuous?) position a bit further. You might be thinking something along the lines of, ‘Yes, nukes are very bad, but be that as it may, on the whole we’ve made significant improvements. We discovered insulin, eradicated smallpox. We learned about sanitation. We’ve had some people create some very lovely art which we continue to enjoy long after they’ve died. We had labor movements and suffrage movements and civil rights movements. We even went to the Moon, for heaven’s sake!’

And you’re right—it’s true that we here in the Western World (sorry to any readers who may hail from more distant realms, I don’t mean to exclude you) live, on average, very privileged lives. There’s a saying about how even the most ordinary, unimpressive person living in a studio apartment somewhere in any modern-day city enjoys greater pleasures and comforts than the Caesar of Rome did in its heyday. Caesar didn’t have hot showers or Doordash deliveries or options for contraception or luxury ski resort getaway vacations.

What’s that? You hand-downers want to rebut? All right, all right—he might have had indoor plumbing, countless servants to cater to his every whim, harems of dispensable concubines, and the Italian Alps on his doorstep, but you get my point. Even the richest, most privileged people of history could never have dreamed of living the way that we do. Our technology and social institutions have developed at astonishing rates since the time of the great Emperors, or the feudal fiefdoms of medieval Europe, or the scientific advancements of the Renaissance, or the economic growth of the Industrial Revolution, or indeed, even since the last bomb was dropped in WWII. Ignore everything else—the Internet alone is an unfathomable advantage to us, though we hardly use it to further our personal or collective potential. At least, not regularly. The entirety of human knowledge and experience at our fingertips, no more than a click away? And now the advent of AI, and perhaps not long after it, AGI? We’re practically gods, creating alternate life forms to carry out tasks for us and satisfy our every whim.

So, when those few of us raise our hands to say that, yes, life is objectively better now than it ever has been (with the notable caveat that it may still not be subjectively better) an interesting question thus arises: might there be a point in time somewhere in the future where life could become…perfect? If we extrapolate far enough on our collective progress—and before we’re done, we’ll certainly evaluate if indeed any true progress has been made—is it feasible that something like a utopia might eventually be achieved?

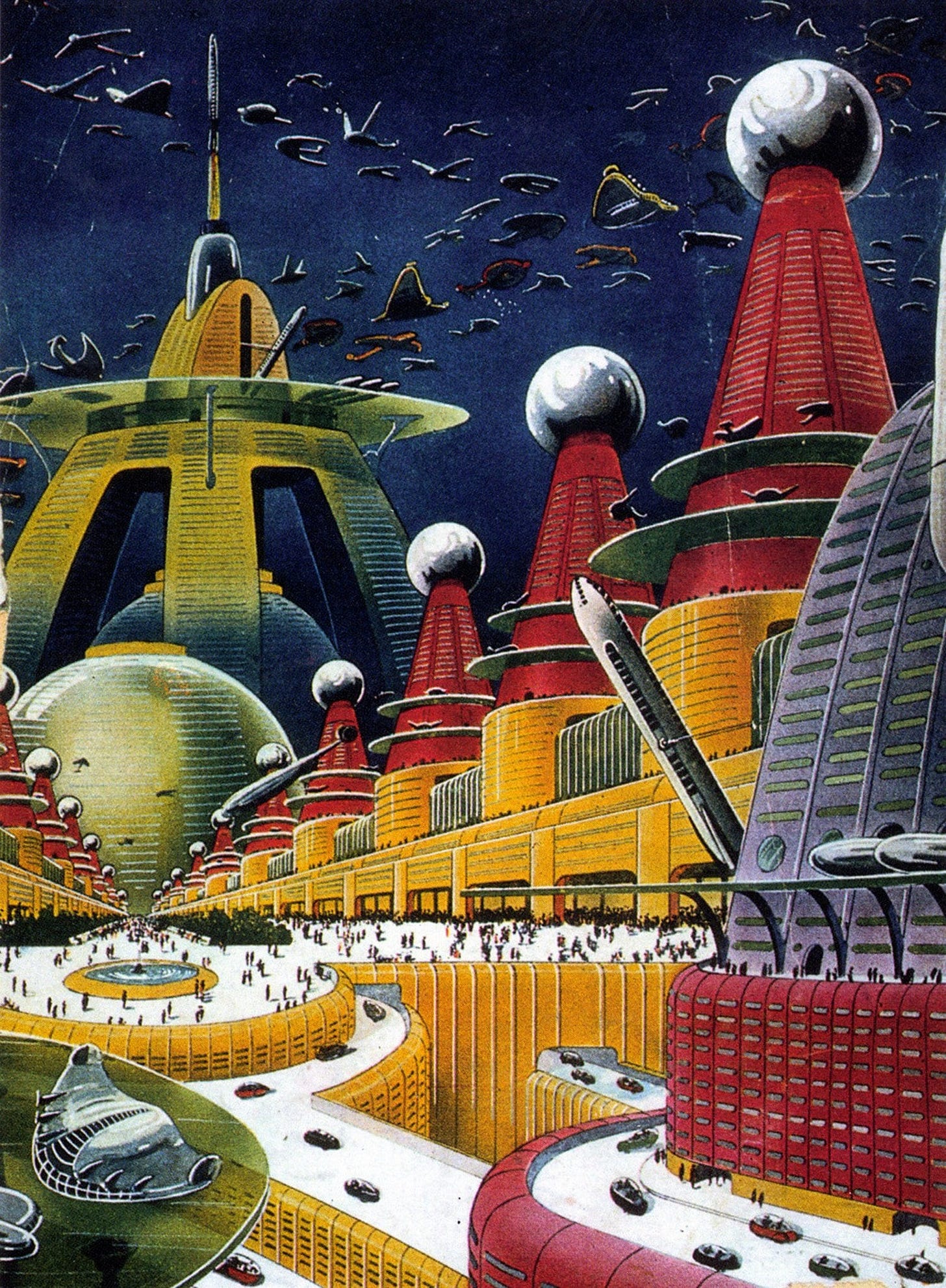

Science fiction literature is filled with visions of failed utopias. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. The Time Machine by H.G. Wells. We by Yevgeny Zamyatin. The City and the Stars by Arthur C. Clarke. But time is on our side; we’ve got somewhere in the ballpark of a billion years before the Sun explodes to figure out how to build one. And even then, if we can invent a way to become an interstellar species, the sky is truly the limit. The very horizon of the universe would stretch ahead of us, and only the end of time itself would be our final limit. On timescales of that sort of length (it’s estimated that the light of the last stars will burn out in about 100 trillion years) isn’t it fair to say that it’s possible we might, with the aid of astounding technology and innumerable years of experience under our belts, build something akin to a perfect world? Just as a matter of inevitability, I mean. When you trace the trajectory of our past and follow it into the future, doesn’t the ‘moral arc’ of humanity bend toward self-improvement?

We’d have to survive a good deal of imperfection in the meantime to find out. And given our very, very imperfect societies—downright dystopian, you might say—it’s hard to imagine us living through the next century, let alone the next countless millennia.

But let’s not give up hope just yet. All of us, whether we raised our hands or not, can probably imagine how things might be better. Not perfect, no—but incrementally better. We can even imagine how we might achieve such improvement. We might even have an idea or two about how we as individuals can make the improvement happen, right here, right now, while we’re still breathing.

We don’t have to wait until we get to heaven to start making a difference. To heal that which has been hurt. We can begin with those closest to us—neighbors, friends, family. Drops in an ocean, sure. But you can’t say that each drop doesn’t change the whole. If enough people think like that, feel like that, act like that, it’d be something like a sea change. That in itself might be the single best reason to believe that utopia, if it can’t exist out in the world, it can exist in the mind.

Jesus did say his kingdom ‘was not of this world’, after all.

Future Atomic City by Frank R. Paul

Culture wars

As I pondered the idea of a man-made utopia actually coming to fruition, one set of science fiction novels in particular came to mind: the Culture series, by Iain M. Banks. The first story was published in 1987, but in more recent times these novels have re-entered the limelight, namely due to a certain billionaire’s somewhat ironic appreciation for them. This glowing appraisal is ironic because Banks more or less intended his stories to be depictions of a post-scarcity, socialist utopia of the future—the kind with no need for billionaires, or indeed currency of any kind. ‘Space Communism’, as Banks’ fans often cheekily describe it. Someone who gives these stories a cursory skim might emerge on the other side believing Banks was some kind of technocrat intent on ushering in the age of AI superiority (which is likely what this billionaire in particular did), but this is a shallow read of the material. The hyper-advanced society featured in the Culture stories is certainly empowered by their technology, but they do not use it to indulge such base instincts as greed, enmity or megalomania. Rather, they have carefully constructed a social order where there is no hierarchy, no coercion, no want or need that goes unsatisfied. No one ever goes hungry; everybody has unfettered access to the pleasures of this life. Those pesky few who don’t ‘play by the rules’ aren’t punished or thrown in prison, but are patiently tolerated, chided and, more generally, put under social pressure to straighten themselves out. The doldrums of managing such a complex sociopolitical and socioeconomic structure are outsourced to the vastly intelligent and benevolent AIs called ‘Minds’, which—having no interest in domineering over their subjects/patrons—carry out their duties with faultless efficiency. This in turn affords total freedom to the citizens of the Culture to life their lives unimpeded by things like work, politics or civil administration. Indeed, whenever there is conflict, it is not the Culture itself that is the source of the trouble, but rather the other, less advanced civilizations that populate the galaxy and stir up controversies. These unenlightened barbarians, for one reason or another, cannot abide the utopian ideals of the Culture; many of the plotlines in this series focus on the ethical dilemmas that arise from these disparate worlds colliding.

What’s most interesting to me about these novels is that they offer a vision of what might be considered a workable model for a utopian society of the future. These kinds of stories are few and far between, at least to my knowledge. Sci-fi, when it does feature anything like a ‘utopia’, usually leans into the idea of how such laudable intentions went astray, resulting in hellish, dystopian nightmares. Either that, or they veer in exactly the opposite direction, serving up portents of apocalyptic proportions, where human civilization has ignored every warning and plunged headlong into the abyss. Banks’ Culture, then, is a refreshing take on what might lie ahead of us if we could just get our act together and stop killing one another. Who knows—we might actually be able to build something like a utopia for ourselves.

Does it seem naïve to think such a thing? I suppose it does, when we consider all that is wrong in the world today. We are immersed in an ocean of suffering, as I described in my previous piece. But if science fiction can use its predictive powers to imagine all the ways we might use our technology to destroy ourselves, I think it has equal power to show us how we might save ourselves from destruction. I can’t necessarily imagine what advancements exactly those will be—I think AI presents as many issues as it appears to solve, for instance. So that’s why we need to think a bit bigger, if we’re going to get anywhere. Rather than look at a specific development and try to argue how it might improve our lot one way or another over the course of time, I want to zoom out as far as we can go. This far out, we can’t differentiate between specific developments to weigh up their net benefits or drawbacks. We’re operating on the macro scale, not the micro. As we look out to the unfolding eons, the question now becomes: is it possible that, given enough time, will all of these small improvements (insofar as real improvements exist, and we’ll get to that) eventually amount to a perfect society—one that has eliminated all the awful things which plague us today? If not, why not? What is it that might hold us back from ever creating our own utopia, if time and ostensibly technology are not factors?

I won’t be arguing whether it’s likely that we construct a Culture of our own, just to be clear. The way things are looking now, I’d have to say it’s decidedly unlikely that we could achieve anything like the interstellar citizens of Banks’ novels did. But again, that idea is thinking too small, too immediate. We want to look to the temporal horizon, and then past it, if we can. We want to consider whether or not it is possible to create heaven-on-earth, given all that we know about the human story thus far, and exercising our ability to extrapolate it into the future.

There is a limit to how far we peer, it’s true. We can’t see past the end of the universe itself. I imagine beyond this point is God’s domain—a realm without time, a realm of eternity. Maybe it’s after all is said and done here on this mortal plane that God’s great plan to redeem all Creation to Himself reaches its final act, and we are restored to Him in heaven. That would make sense, wouldn’t it? If there is a heaven, it must exist outside of time. We have to keep marching at our steady pace until time itself ceases (if it ever does—the acceleration of the universe’s expansion might indicate that there is limitless time ahead of us, since time is so wrapped up in what we think of as ‘space’.) Only then will we be made ‘new bodies’ and enter into this heaven. Only then will the world be made new again.

Sounds lovely—this world we inhabit could really use a good scrubbing-up. I genuinely believe and hope that we have paradise waiting for us, and that light will overcome darkness in the end. But, in the meantime, what are we working toward? Why do we care about improving our world in the here and now, if heaven’s gates will be opening to usher us in soon enough? Wouldn’t it just make more sense to rest on our laurels? (And, indeed, Christians have been guilty of just that sort of thinking in the past—putting too much emphasis on preparing the soul for its journey into the beyond, and thus ignoring the very real suffering of people living today.)

That’s the question at the heart of this problem. We certainly do strive to make our lives better, and by the same token, our world a better place to live. We do it—it would seem—on our own, by our own power. Jesus is preparing us a place in his Father’s house, but for now, we’ve got to make do with this run-down old shanty we’ve been squatting in for the better part of 300,000 years. But isn’t it true that if we keep at it—filling in the holes here, laying new floor panels there, maybe inserting a couple of glass windows to keep the cold wind from ripping through the walls at night—we might end up with something a bit better than a hovel? Maybe, we could even build ourselves a palace.

Maybe we’d be able to say that we did it all ourselves. ‘Thanks, but no thanks, God. We’ve created our own heaven here on Earth. Whatever You’ve got in mind after it all goes dark, it can’t be any better than this.’

Sound about right?

Without a map

Let’s avoid putting words in God’s mouth and take a closer look at what He seems to say about all of this. In my pre-writing discussion on this topic with my dad (a pastor, in case you needed reminding) he laid it out stark and clear: Biblically speaking, yes, utopia can exist this side of heaven. I hadn’t expected that answer, but it turned out he was being a bit cheeky. Utopia can exist in this mortal plane because it already did.

He was talking about the Garden of Eden, of course.* If we accept that the story of Genesis, while symbolic, played out in some fashion with real human beings who lived real lives at some point in the distant past, then we would have a precedent for some kind of ‘perfect society’ existing on Earth. What might it have looked like? That’s a whole ‘nother essay topic, right there. I’ll only posit that it may have had something to do with humanity’s ‘innocence’—a childlike spirit that our earliest ancestors must have had when they first awakened to themselves and the world around them. These humans may have, for a time, lived in peace with each other, nature and God. (Not sure what I’m getting at? Read my piece Kubrick’s Monolith: A Plausible Genesis Account? and it might clarify my thinking on the issue.)

However, the Fall comes very quickly—basically page 2—and the story subsequently shifts to focus on God’s ongoing, painstaking effort to restore humanity and Creation. So, whatever utopia we might have once enjoyed, it’s long gone. It’s fair to say that it likely won’t be returning anytime soon, I think. And before you mention the Rapture, just know I’m way ahead of you. We’ll be cracking open that can of worms in due course!

So, we haven’t really gotten anywhere in answering our initial question. Sure, maybe an Earthly utopia did exist, somehow, but what about in our future? Could we build one for ourselves eventually? Here the story of Genesis points us in the opposite direction—no, we can’t, because we humans have become corrupted. Corrupt things can’t produce something perfect on their own; they’ve been compromised. Their intentions and methods are suspect. The Bible even tells us that we can’t comprehend just how corrupt we truly are. Here’s a particularly sobering passage for you to consider:

The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked; who can know it?

Jeremiah 17:9

It’s at this point that a good few of my readers are likely having a visceral reaction to some of the ideas I’ve mentioned, namely Fallenness. It doesn’t sit well with people, this idea of there being something terribly wrong with the hearts of all human beings. And no wonder. All human beings—even my harmless old grandmother? My neighbour who volunteers at the homeless shelter every weekend? Don’t tell me you think my newborn child is somehow born ‘wrong’!

I was having a great discussion here just a few weeks ago with an atheist fellow (great person, by the way) whom I’ve struck up a correspondence. This person cited the doctrine of Original Sin as being one of his chief complaints—scratch that, revulsions—about the Christian faith. What kind of religion would proclaim a good and loving God who curses the world He created to suffer and die? Who curses the souls of innocent children, dooms them to suffer and fail?

I mention these things because I recognize they often come from a place of honesty. It is very hard to grasp the role of evil in our lives. We know how real it is, but we can’t seem to figure out who’s to blame for it. Or, we think we know, and we’re very unhappy about how little justice there seems to be. People who level criticisms at Christian thinking on these topics have every right to do so, and more often than not, are coming at it from an angle that I think God Himself would approve of. Why do we tolerate so much suffering? Why equivocate and obfuscate about who deserves what, and who doesn’t? Christians especially. Shouldn’t Christian people be leading the charge in terms of correcting earthly injustices? If they’re not, just what is their religion worth?

Not a lot, if it isn’t countering the forces of evil at work in the world. I hope that’s not an audacious claim to make. If Christian faith is to be worth anything, it should be worth something here—right now, in this world! It should be a shining light that burns away the darkness and leads others to safety, grace and peace. ‘Storing up treasures in heaven’? This is done by sharing treasures on Earth; by loving one’s neighbour, by visiting the prisoner, by clothing the needy, by feeding the hungry. And, I’m sorry to say, but Christians have not exactly been leading by example. I’m painting with a very wide brush, I know, but come on. Seriously. As a group, Christians are just as guilty of failing to represent God’s loving nature as anyone else (and the worst part is, we should know better!) Remember the famous quote:

I like your Christ, but I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.

Mahatma Ghandi

I’m not bringing these things up to castigate Christians of the global church, but to highlight an important truth. We aren’t perfect. We don’t even fully grasp how imperfect we are. And those of us who should know, often don’t as as if we do. So, if we’re wondering if we have it in ourselves to build a perfect future society where everyone is loved, where there are no prisoners, where there is no nakedness (unless it’s the perfectly innocent, Garden of Eden kind?), where there is no hunger, we can be quite certain that, no, we don’t.

We need outside help.

We need our ‘hearts of stone’ to be replaced with ‘hearts of flesh’.

This is where some of the New Testament ideas become really important. The Apostle Paul writes a lot about the idea of repentance in his epistles. In essence, he shows us that God has made the help we humans need available—the help to understand right from wrong, to avoid temptation, to stand up for justice and truth. To love one another, essentially. To be changed into people who are capable of such love. With God’s intervention, we can be better than what we are. The divine spirit that is in us, that animates us, that is us can be redeemed and turned to the good. What it takes is a recognition of the ‘Fallenness’ within us—a genuine grasp of how we have gone astray, how we need outside help—and then a commitment to change.

Nobody ever said it would be easy. But it would be impossible without God. And that would make sense, if God is actually God. By definition, God must be the ultimate source of all that is good, noble, true and beautiful. God is love. If you aren’t oriented towards the highest good, then you must be oriented toward something else—and that something else can’t be the highest good, the source of good. That seems like a pathway toward something other than ‘ultimate good’. A road to lesser good, then. A road which then forks, and forks again. Before you know it, you’re far off in the wilds, lost; nothing to guide you and no sense of direction. You thought yourself a trailblazer, but what you need now—what you always needed—is a compass to reorient you. And, if perfect good exists, then there’s really only one direction worth heading in.

The arc bends toward justice

Thus far, my conjecture may have come across as quaint or overly idealistic. I may not have appropriately reckoned with the sordid state of affairs in the world today to have convinced you that I take the issues seriously. And I get it, I really do—when I was first thinking about this topic, I started from a position of questioning whether any real progress has been made at all in improving the human condition over the course of our entire history. We’ve made technological improvements, of course, but have we made moral ones? How can I say with a straight face that the world has never been better when there are still so many facing starvation, deprivation, racism and gender-based violence, sexual exploitation, and any number of other great evils?

I don’t know if we’ll ever be rid of those wicked things, to be honest. But despite them, I do believe that moral progress is possible. I believe that we have already progressed a great deal. Take the issue of slavery, for instance. It’s certainly the case that slavery still exists in the modern day, albeit by different names: indentured servitude or human trafficking. There are untold thousands, even hundreds of thousands for whom this unconscionable evil defines their lives. Some might scoff at the idea that slavery was ever ‘defeated’—sure, we might not have the Atlantic Slave Trade anymore, and the Romans might not still be selling their own children into slavery, but slavery itself is still very much a force shaping reality as we know it. Evil has simply morphed alongside us, or rather, morphed along with us, borne in the same wicked hearts that spawned every other terrible thing ever done on this Earth.**

And yet… While none of that is untrue, it doesn’t account for the changes we have witnessed as our societies have developed and changed across the centuries. To take the case of slavery once again, it is certainly the case that we have shifted our collective conceptualization of slavery from one of normality to abnormality—and indeed, even abhorrence. We have grown in moral stature since the times of the Romans. We recognize and see how evil this practice is, and we work—imperfectly, of course—to stamp it out across the globe. Simply put, we don’t see the issue the same way anymore. I wouldn’t say that we ‘know more’ now than we did then, because I’d imagine that the Romans and the slave traders knew the things they were doing were causing harm; they just didn’t care and saw these slaves as less-than-human, and therefore unworthy of treatment as such. There’s something in that, too: even the Romans and the slavers recognized the value of a human life. They certainly treated their rulers and business partners with dignity and respect. What’s happened is that, in our current times, we’ve expanded the ‘human’ definition to include more people than our ancestors ever did.

So, that looks like progress, albeit of the slow and painstaking kind. But if progress is indeed possible, then shouldn’t that be cause for great relief and celebration? Recall our original question: if we were given enough time, does it stand to reason that we might eventually perfect ourselves? Keep building progress on top of progress, brick by brick, righting wrongs wherever we find them? Will we someday live like philosopher kings, steeped in cosmic wisdom and high-minded moral doctrines?

Ian M. Banks might like to think so. But there are two key human failings which the Culture does not or cannot adequately address:

Existential evil exists.

Human corruption exists.

I talked more about existential evil in my last piece Is Consciousness a Gift or a Curse?, so I won’t repeat myself here. The issue of human corruption I believe I have outlined sufficiently already. The sum total is that these two factors—both of which are rooted in the metaphysical reality which gives structure to the local reality we inhabit—act as obstacles to achieving moral perfection which we cannot overcome on our own. Any human attempt to construct utopia is by necessity doomed if it does not take into account how to deal with the fallibility and rebelliousness of the human heart (let alone the cosmic forces seeking to disrupt God’s good designs for His Creation). And, if it did by, say, transforming us into something transhuman, thereby eliminating the risk of corruption (I’m thinking along the lines of genetically altering humans so that they can’t think for themselves and make bad decisions), it would raise a pertinent, troubling question: would we even be human anymore?

Let’s get more grounded with this so I can show you what I mean. We can look at the Culture to see how this ostensibly utopian society isn’t really viable when we reckon with human fallibility in a serious manner. The Culture operates as ‘perfectly’ as it does because it assumes that humans, once they have everything they could want or need, will cease to fight, compete, argue, steal, denigrate, or just generally become disagreeable toward one another (and their environment). I think it’s fair game to imagine a futuristic society where advanced technologies have made resource scarcity a thing of the past, and every living being has total freedom to pursue whatever pleasures they so desire. The problem is that even if 99.99% of the Culture’s population is participating in this system in good faith, it only takes one person to ruin it for everyone. One bad seed spoils the entire civilizational bunch. One bite from the forbidden tree changes the entire course of human history.

It doesn’t matter what motivates this choice for evil over good. The point is that where choice is freely available, as we are to believe it is in the world of the Culture, the choice to destroy it all is, by definition, available as well. ‘Some men just want to watch the world burn,’ to borrow a phrase from a wise butler. A utopia that attempts to cater for every human need in the hopes of staving off widespread anarchy is missing the fundamental point, at least from Christian perspective: you can’t solve the Problem of Evil by giving people enough food, clothes and medicine to satisfy their earthly desires. The trouble lies deeper than that. People have heavenly desires, too. And hellish ones.

If Banks wrote the Culture series to be an exploration of Space Communism, we should acknowledge that, if history is anything to go by, Communist societies are remarkably susceptible to bad actors. Lenin envisioned a Russian state that served the vast working population in equitable and egalitarian terms; Stalin seized the reins and transformed his dream into a nightmare. There are Christian examples as well: think about how the Puritan movement, originally motivated by the laudable goals of religious freedom and spiritual revival, devolved into narrow-minded, legalistic zealotry. Think about Calvin’s Geneva, where the effort to establish a ‘model Christian society’ ended up resorting to draconian enforcement techniques when it turned out that its citizenry wasn’t altogether keen to strenuously observe austere religiosity. These examples reveal how no human-designed system can bring about true paradise, despite its best intentions. The problems we need to solve to ‘get back to Eden’—existential evil, internal personal evil—are beyond our powers.

We have to remember that we were never meant to be morally independent; we were created to have dependence on God. ‘Fallenness’ is what happens when we live outside of this purpose. It is a kind of brokenness, but not one in which we are hapless victims. We are willful, complicit. We participate in this brokenness every time we lie, cheat, steal, hate, resent, or act selfishly. We fail to love one another almost daily.

Thank goodness there’s Someone out there who cares enough to fix us. To fix this broken, unloving world we’ve made. We might not see it in our lifetime—okay, we almost definitely won’t—but we can have hope. Hope for the utopia that is to come, which is not of our making, and therefore faultless. And while we wait for the house to be prepared? We can make ourselves busy by partnering with the Spirit of God and fixing what’s broken here on Earth. We’ve done it before, and I think we’re even doing it right now; both in small, personal ways, and in macroscopic ways that will shape the societies of tomorrow.

So, take some courage, knowing that we’ve good things ahead of us. Take some satisfaction as well, knowing how much ground we’ve covered to get where we are. Just don’t get complacent. Don’t stop fighting ‘til the fighting’s done.

And it won’t be done until, one day, the bending arc comes down to meet you right where you are. Something to look forward to, I suppose.

A utopia not of our own making, but of God’s.

*Side note: My goodness, how often we revisit this story! It truly is jam-packed with meaning. We keep coming back to the Garden, again and again, and we always seem to distill something new… It’s no wonder to me that the story has survived as long as it has. I imagine it will continue to be told long after we’re gone.

**That strikes me an interesting thing to note: homo sapiens, it would seem, are the only species to have ever committed immoral acts, because they’re the only ones (that we know of) who have any awareness of morality of all. We are singularly guilty of every evil thing that has ever happened in the history of the planet!

I could write a novel commenting on this (in a good way!) but short of that...

* My hand shot up right away

* The atheist thought the problem concept was Original Sin rather that Perfection? Dude that's my problem with atheists in a nutshell right there!

* The problem is the idea of perfection itself. It's a poorly formed idea in the first place. It is necessarily in the eye of the beholder, and one man's utopia is another's hell.

* Specifically, I think Brave New World was a successful utopia, and we only view it as a dystopia because we actually value a bit of struggle.

* Given the above, Christian salvation is less about ending suffering than it is changing our relationship to suffering. Utopia comes from within, and exists wherever you carry it.

Just some thoughts! Great essay!