Let’s face it: things are looking grim. The world that we thought we knew is crumbling to dust. The frightening specters of war, famine, and disease rise from the cracks in the once-solid ground below. In times like these, people are looking for a sign. There has to be something we can turn to to show us the way forward. As darkness descends, we search for the light. What can make it all make sense?

But there’s nothing. We raise a cry to heaven, and there is only silence. We look back to the ancient stories for guidance; we remind ourselves how we came through trials and tribulations in times past, and we are struck by the clear and immediate presence of the divine. Where has it gone? Our ancestors had omens and portents to show them the way forward—they consulted the spirits, threw bones, read the stars, examined the tea leaves, meditated on the mountaintop, heard the voice of God whisper in their hearts and resound across the valley.

Not so with us. Why are there no more pillars of fire to lead us through the dark of night? Why aren’t there ghostly hands writing messages from the beyond onto our walls? Why can’t holy people raise up prayers to stop the Sun as it tracks across the sky? Why can’t we call down plagues upon the evildoers to see them brought to heel?

The age of signs and wonders appears to be long gone. Those stories we read of the gods boldly and dramatically intervening in our world are mysteries to us now. Did the ancients hallucinate these things, or merely lack the language to describe such phenomena? Or, perhaps the accounts are true, and for some reason, heaven is now closed to us. Perhaps we have shut ourselves off—climbed up as high as we can in our towers of scientific rationality, and in so doing, have lost sight of the metaphysical ground upon which the foundation of our being is laid.

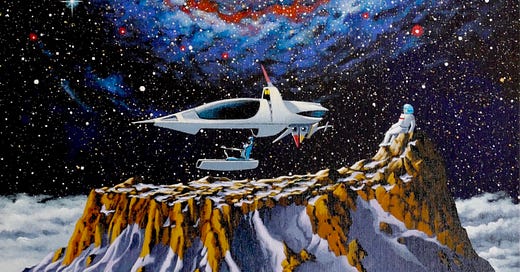

But now a new age may be dawning. We may yet rediscover that sense of wonder as we behold the vast expanse of the cosmos. It’s closer now than it ever has been before. We have taken our first tentative steps beyond our atmosphere, flitted about in airtight canisters, bounced across the surface of the Moon, snapped photographs of the yawning abyss and its myriad of celestial spectacles. We’ll likely go further still, perhaps far enough to visit neighbouring planets. When we do, if not sooner, we might reawaken that long-dormant fascination with that which we cannot explain, that which is beyond our comprehension. It’s all right there—it always has been, staring us in the face.

Infinity is at our doorstep. Infinity is within us. The universe extends forever, inward and outward, from the outermost reaches of the cosmos to the boundless infinitude of the quantum field. We occupy the center of these two eternities, and we fool ourselves into thinking that what we behold from this vantage is all that is truly ‘real’.

Maybe we are the sign. Maybe we’ve known the way forward all along. Maybe this is but a moment of weakness—a temporal lapse into blindness, arrogance, egoistic self-interest. Maybe all we need to do is wait patiently, because ‘the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice.’

Maybe. But we can’t deny it: to see the heavens crack open, to hear trumpets sound and witness tongues of fire descend… That would certainly shore up any doubt that the world is held in capable hands.

Artwork by Steve R. Dodd.

Everything, everywhere, all the same

Our best understanding of cosmology would indicate that, at a sufficiently large scale, the universe should appear homogenous. This is referred to as The Cosmological Principle. The reasoning goes that, if you were look down at the universe as God must—infinitely far away and capable of beholding its entirety within the scope of your gaze—it would appear as uniform. All matter in existence is evenly distributed across this vast expanse; no one part is any brighter or darker, more dense or less dense than any other.

Of course, we know that the universe is different from place to place. I’m here, writing this, and you’re there—wherever you are—reading it. Our spatial positions are different. For instance, the room I’m writing this in might be extraordinarily dark and dismal (just the way I like my writing space: something like a cross between a wizard’s lair and a fallout shelter) while your cozy little reading nook radiates warmth and comfort, allows the sunlight to stream in and tickle the tips of your toes peeking out from under your weighted blanket.

Very different, our two little zones of the universe.

But we can only see this difference because we are so small and ‘zoomed in’ enough to recognize that, on much smaller scales, matter is distributed somewhat unevenly across the field of spacetime. It’s this little quirk that many physicists think explains the manner of the universe’s expansion since the Big Bang; for some reason, when it all went kaboom, some pockets of the rapidly expanding cosmos were a tinge cooler than others. When those bits expanded as rapidly as we know they did (from studying the cosmic radiation background of the universe) they ultimately resulted in wildly different concentrations of matter in various places. These concentrations would allow for cosmological structures to form; concentrated matter would, by force of gravity, condense to create galaxies and stars. Those stars would further condense matter to form heavy elements—the same ones all other physical structures are constructed from, from planets to single-celled amoebas to bamboo trees to capybaras to human beings.

And yet, the universe is so incomprehensibly vast that all these concentrations and complex structures are invisible from the vantage point of one standing far enough away to take it all in at once. The Big Bang, so we think, tossed a universe’s worth of matter in every which direction upon ignition. From then on, the laws of physics did their work, applying themselves in exactly the same manner in all regions of this infinitely expanding space. The result was a cosmos shepherded along its evolutionary path by a uniform governance, thus becoming uniform in its overall shape and character.

That is, until we discovered the Big Ring, and everything I just wrote about the Cosmological Principle was called into question. Suddenly we discovered that our fundamental assumptions about how our universe operates may, in fact, be totally wrong.

Or maybe, everything’s working exactly as it should be, but God has seen the sorry state we’re in down here on Earth, and—either out of a sense of humor, or because He’s trying hard to get our attention—and has decided to give us a sign.

Will wonders (never) cease?

Simply put, the Big Ring should not exist. It is too massive, too gigantic, too mind-bogglingly enormous to properly account for. It dwarfs galaxies and even galaxy clusters in scope. It defies our best understanding of physics. One could be forgiven for thinking its existence is simply a mistake—no doubt there are a great many scientists working on this exact theory.

It was only in the past few months that all of this came to light. Alexia Lopez, a PhD student at the University of Central Lancashire in the UK, made the discovery (itself trailing on a previous discovery of hers called the Giant Arc, a superstructure with similar attributes to the Big Ring). If you’re interested in reading more about her discovery, you can check out this article. In it, the author states:

Cosmological theory suggests that the largest structures — in the form of chains of galaxies and galaxy clusters — that BAOs could form should be, at most, 1.2 billion light-years in length. Yet, the circumference of the Big Ring and the length of the Giant Arc dwarf this constraint. To put into context how immense these superstructures are, the Giant Arc is one-fifteenth the radius of the whole, visible universe.

Taken together, the Big Ring and the Giant Arc are the largest cosmological structures known to mankind. For its part, the Big Ring is a collection of galaxies and galaxy clusters arranged into a distinctive circular shape, 1.3 billion lightyears in diameter. Its circumference is estimated to be about 4.1 billion lightyears. For comparison, the Laniakea Supercluster—of which the Milky Way is a part—stretches a mere 520 million lightyears from end to end. Both of these structures are located incredibly deep in space, far enough away that we see them as they were approximately 9.3 billion years ago, as that’s how long it takes their light to reach us. What is more, since they appear to be in relatively close quarters with one another, it suggests that the two may be in some kind of as-yet-unknown physical relationship which may point to the existence of even larger cosmological structures.

If this hasn’t quite blown your mind yet, it really should. True, we’ve no real frame of reference to understand the scale of these structures. But the idea that the Big Ring defies common understanding—that it rips up our best models of the universe and laughs at our meager grasp of astrophysics—should stop us in our tracks. We should take a moment to wonder at the things in the natural world that elude explanation. How can this be, when we are so certain of the sciences and their ability to tell us all we need to know about the world in which we live—a world that is measurable, predictable, and concrete?

This is where we can begin to discuss the idea of miracles.

But before I travel too far down that road, I do want to state that I’m not arguing that the Big Ring is by necessity a miracle. Our more skeptical readers will likely comment that, in regard to my last question, one should maintain confidence in the ability of the sciences to describe natural phenomena, even when said phenomena seem to defy science. Science is, of course, always developing. In fact, we improve our scientific understanding by making mistakes; we posit a theory, test it, study the results and adjust our assumptions accordingly. If our current models of the universe can’t account for the existence of the Big Ring, it just means we need to develop better models. No argument here—have at it! It’s entirely possible that one day we will be able to explain these gigantic structures as the product of physical forces that we can and do understand. Just be aware that, in saying so, you’re making a sort of statement of faith—faith that science can provide the answers you’re looking for. And so I ask: is it really so different to put your faith in something you can’t see, yet trust to be there?

On that note, back to miracles. We’re going to put on our Christian theology hats now for a minute and take a look in the Good Book. We begin our journey by flicking through the Old Testament and, my goodness, there are certainly a lot of miracles recorded here! But we’ll notice that the character of these accounts seems to change over the course of time. In our oldest stories, the miracles are truly wondrous (and terrible)—great floods, great fires, waters being parted and mana from heaven. Some are more modest—the burning bush, for instance—but they’re often followed up by far more grandiose occurrences, such as the Ten Plagues of Egypt. I’m always reminded of one of my favorite childhood movies, The Prince of Egypt, and how magnificently it visualized these wonders/terrors. Check out a clip here if you’d like a refresher. (And the music is killer, too!)

As we move into the New Testament, the miracles become more intimate. Now we read about healings done in remote regions of the desert, witnessed by few, sometimes done in secret. The wildest accounts—including resurrections—are experienced by small groups of people. It’s easy to imagine that when these witnesses attempted to share their stories with others, they were easily dismissed and disbelieved. Water turned to wine at a wedding feast? Right… How drunk were you when this happened? These miracles seem to belong to a different class than those we read in Joshua or Exodus, and certainly Genesis, where the stories are so ancient it’s hard to ground them in any sort of objective, rational reality we might recognize today. They operate on the scale of individuals rather than entire nations. They’re no less miraculous, but still, it’s curious, this change. What could be the reason?

And then there’s the final stage—the post-Ascension period, running up to the current day. We still have accounts of miracles occurring beyond the last pages of Revelation, particularly if we study the lives of the saints in the Dark and Medieval Ages. But when we arrive at the modern day, the time of technological wizardry and scientific preeminence, miracles seem to be entirely absent. We don’t hear in the news of people being healed by the laying on of hands, or of dead people rising from the grave (in the popular imagination, that would likely constitute the beginning of a zombie apocalypse). These things still happen in churches around the globe—and people certainly still believe in them—but, on the whole, they are not taken seriously by the world at large. Most people would generally brush off these stories as oddities, superstitions, or at worst, manipulative deceptions. Some might argue, at a stretch, that certain weather phenomena might be considered ‘miraculous’, or perhaps strange instances of serendipity or coincidence. They’d be well entitled to believe such things, but it’s unlikely that they’d convince many of the same. Whether because of our improved understanding of the physical world or otherwise, we seem as a culture to have moved on from commonly-held beliefs in otherworldly powers intervening directly in our affairs. Those who still do believe such things, we tend to view as eccentric, or even dangerous; mediums, fortune tellers, ghost-hunters and the like.

So, how are we meant to understand the ancient stories we read of these signs and wonders, when we have virtually no point of reference from our own experience? Even those of us who suspect we may have experienced something of the divine—a voice, a message, or just a startling event not easily explained—have difficulty making sense of what we find in the Old and New Testaments. It seems simplest to assume that, on the some level, the stories are made up. Stories interwoven with legend, handed down over the generations, eventually taking on a mythical character. There might be some kernel of actual, hard reality at the core of these stories, but whatever it is is now lost to us. We simply can’t believe that God would act in the ways that he supposedly did all those years ago, or if we do believe it, we’ve a hard time grasping why He doesn’t appear to do so anymore.

Simply enchanting

A theologian whose work my dad loves to read is Richard Beck. He’s got stuff right here on Substack, as it happens, so check him out! Beck describes a ‘theory of enchantment’ which can help to explain why we’ve such trouble making sense of the miraculous stories we find in Scripture. In essence, Beck’s idea is that the invisible world—that of the spirit, of God—exists simultaneously with the physical world. We humans are creatures of both these worlds, possessing physical bodies as well as a spiritual core that exists at the root of all experience, deeper than even consciousness itself (after all, doesn’t an unconscious person still have a soul?) Every once in a while this other world becomes perceptible to us, and it doesn’t happen for no reason. There are forces and wills on the other side of the partition. There is our realm, and then there is the realm of the faeries. We can’t readily understand the nature of this realm—though many try—but, as a bottom line, it provokes us to wonder and search for its meaning. All we know for certain is that our two worlds are entwined, though nowadays it’s become quite challenging to make sense of their relationship.

We exist at the perihelion of scientific materialism. Never before have we understood so much of the nature of our universe, and never before have we been so convinced of our understanding. It is a journey we began, culturally, about two centuries ago. In the 1800s our world was becoming smaller. The darkest corners of the globe were penetrated, and the mystique they contained was dispelled. The Age of Enlightenment had given rise to great thinkers who had managed to create enough cognitive space for men like Charles Darwin to come truly new ideas; ideas which likely would have had a great deal of trouble getting off the ground in the days of Church-dominated culture and society. Empiricism became the marker of knowledge and wisdom, and for good reason. Outdated, religious models of the universe’s inner workings had proven unable to keep up with the advancing capabilities of science and rationality to explain the same things: why are we here, where did we come from, where are we going. Let’s leave aside that these scientific advancements didn’t have very good answers for what it all means, as that’s a different issue. Science itself isn’t altogether concerned with explaining ‘meaning’, because that speaks to values and moral preoccupations, whereas science operates in the domain of the demonstrable, the irrefutable, the empirical.

In the end, what we gained in scientific understanding cost us in ways we did not quite grasp, until, perhaps, our current moment. Scientific materialism narrowed the bounds of what could be considered ‘real’ in the world, reducing reality to that of that which can be seen, heard and touched. The magical realms our folkloric heroes, monsters, ghosts, and (who could forget?) faeries inhabited have been demolished. Determinism—the ultimate realization of this approach—holds that everything in the universe, even our own behaviour, is down to the physical interaction of particles. According to this view, we humans are nothing more than fleshy automatons following biological programming. Biology is, of course, applied chemistry, and chemistry is applied physics. Particles interacting, nothing more. No free will. No future, even; every particle in motion now was set in motion during the Big Bang, which means its path through the cosmos was pre-determined (there’s the reason for the name) from the very inception of the universe. If one had a powerful enough supercomputer to quantify this and calculate the trajectory of each and every particle from that moment forward, one would be able to predict the entire story of the universe as it unfolds, right up to its inevitable demise.

Now, I’ve no quarrel with the determinists; they’re doing their due diligence in practicing what they preach. Scientific materialism admits only that which can be proven scientifically. That limits the range of acceptable evidence to hard, ‘material’ proof only. And so, they have followed this idea to its final conclusion. I admire their stoic adherence to their own ideology when it reduces all of human experience and beauty—foremost among which is love—to nothing more than chemical processes! Bleak for certain, but I think the determinists would say it’s only fitting; we live in a bleak world.

But is it only bleak because we’ve become disenchanted? Have we lost touch with that part of ourselves that is attuned to the other world, the world beyond particles and facts and laws? I’m inclined to think we have. There is more than is real than we can measure. I can’t measure how much I love my children. What an absurd notion—if I could, what would happen when I compared measurements with other parents? Would I find that I loved them less or more than others, in quantifiable terms? Love by definition cannot be quantified, because love is the giving of oneself for another—and we are infinite. A being of infinite complexity offering of itself something of infinite value for the infinite benefit of another infinite being? There’s no supercomputer that can calculate that. It goes beyond the limits of our world, a world which is indeed governed by laws and limitations. Love breaks all these limits. God is love, after all! And God is beyond our world, beyond our understanding. When God does enter into this mortal plane—when love is poured out upon His children—that is when Beck’s two worlds, the spiritual and the material, are successfully melded.

Love is perhaps the greatest miracle of all. How can it be that a species of big-brained apes can love one another? Not always, of course—they do it quite imperfectly—but still. They possess this incredible, unfathomable capability that no other creature seems to.

Is this permissible evidence to advance our scientific understanding of the true reality of our world? For the materialists, no. The truth of love exists belongs to the enchanted world, not the physical. But if we are willing to take on a more holistic perspective of our experience—bring together the spirit and the body in harmony—we might begin to understand the world as it really is. It’s really two, overlapping and interacting with one another. To deny one is to experience only half of an existence.

Under a watchful gaze

So then, what about the Big Ring? Well, if we’re willing to consider that there might be more to it than meets the eye, we can consider if it means something. The signs and wonders of the Old and New Testaments certainly did—either to the nation of Israel as a whole, or the individuals who witnessed them. Their purpose was to point back to an origin point. Burning bushes of all sizes and shapes.

Whether these miracles were bona fide supernatural events or merely ill-understood is beside the point. God, we can say, revealed Himself through them, to specific people, in specific places, at specific times, with specific aims. The Biblical accounts give us fairly clear ideas of what these aims were: to answer prayer, to affirm His presence, or, like Jonah and the storm, to get a message through somebody’s thick skull. We also shouldn’t get the impression that, despite the proliferation of miracles through the Bible, they were in any way regular occurrences. They induced shock and awe in their witnesses because they were shocking (read: unexpected, infrequent) and awesome (read: incredible, undeniable).

And, to be honest, ‘shock and awe’ aptly describes my own experience when I first learned of the Big Ring. God’s great eye, watching over His Creation. Incomprehensibly vast and impossible to explain. What does it mean?

The Big Ring is only our latest discovery of the majesty of God’s Creation. Isn’t the universe itself a miracle? In Romans 1, the apostle Paul writes:

Through everything God made, they can clearly see his invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature. So they have no excuse for not knowing God.

-KJV

When we look up at the night sky, we see evidence of God’s presence. He’s the author of the universe. The same is true for the deepest trenches of the ocean, where incredible creatures live in confoundingly inhospitable conditions. The same is true of us; strange creatures who possess something called ‘brains’, the single most complex structures in existence. Somehow we evolved these things, all on our own? Somehow they give rise to a gestalt phenomenon we call ‘consciousness’?

It doesn’t mean that these things aren’t exactly what they are—physical material arranged into various shapes. The Big Ring is made of galaxies and galaxy clusters, which are in turn made of stars, themselves made of gases, themselves made of atoms, themselves made of even smaller particles. But the Big Ring can also be a sign pointing back to that ultimate originator, standing behind the Big Bang, standing outside of time and the universe itself. We can look at it, study it, wonder about it. And if we open our minds to the idea that we might be looking at something more than just dust and light—if we recapture some of that lost enchantment—we might see it as an integrated whole. We might allow some of that mystery to trickle in and feed our parched souls. We might wonder how—how can it be? And when we do, we might begin to move in a new direction. Somewhere along the way, we might find something we never thought possible—something which, unless we’d opened ourselves to it, we would have dismissed out of hand as nonsense, fantasy. Unreal.

See, the faeries never left us. They didn’t cease to exist because we stopped believing in them. They just built bigger and better rings.

The problem with miracles is that they postulate the exceptionality of some things but not others. Yes, the Big Ring is truly miraculous; but what about the Milky Way? What about our own Sun? What about the flowers outside my window? Each of these phenomena has been seen as miraculous or infused with the spirit of divinity by some cultures and some people. William Blake described his ability "To see a world in a grain of sand. And a heaven in a wild flower." This is the human imagination. You may see it as a spark of the divine or as a transcendent human capacity born of evolution. Either way, the world is full of miracles for those who are willing to look.