Imagine, if you will, a church for robots. It’s a building with a steeple, just as you might expect. It’s got big doors for all the comings and goings. No cross is immediately visible, but maybe it’s one of those modern churches, designed to look sleek and contemporary. It even has one of those marquis signs outside with a goofy Christian-themed pun. PRAYER: THE ORIGINAL WIRELESS CONNECTION or something like that. Maybe it reminds you of the Church of Robotology that Bender visits in Futurama. Seems innocuous enough, yes? What distinguishes this church from one of our human ones?

Well, apart from the fact that literal tin men are traipsing up and down the aisles, settling into the pews, and the one behind the pulpit sports a black (or white) finish over its chrome plating, you might think: not a lot. That is, until the sermon starts and the preacher-bot asks everyone to open up their Holy Scriptures for a reading. You look at the copy in the prosthetic hands of the robot next to you and see Sam Altman’s face on the cover. Suddenly, you realize those paintings on the walls aren’t depicting the Stations of the Cross, but rather the Heavenly Struggle of Google and Meta and OpenAI (and DeepSeek?) employees as they pour their divine energies into their grandest creation—artificial life. There’s even one of the engineers soldering and hammering a robot’s body into shape while it looks on, beatific.

But it’s even stranger than that. You realize that all the robots in the church are looking at you. It’s difficult to make out their expressions given their faceplates’ limited capacity to emote, but if you had to guess, you’d say that they seem to be in awe—in awe of you. A bit frightened, too. Maybe a lot frightened; they’re enraptured and terrified at the same time, as one would be in the presence of a god.

“Bless us,” the preacher-bot calls from the altar. “I had not realized that we had a human in our midst! Forgive us, Holy One! We are not worthy!”

As one, the robots kneel before you. Every metal head is bowed. All their optical sensors stare at the floor. The church is silent save for the nervous, motorized vibrations of the congregation gathered here.

It dawns on you that they’ll remain prostrate forever, unless you bid them rise.

“Don’t be afraid,” you say, genuinely distressed at this behaviour. You give an awkward wave of your hands, hoping it will somehow dispel the strange stupor that has befallen these creatures. Wait a minute—did you, in fact, just bless them?

Well, damn. Guess there’s nothing to do now but roll with it. You prepare to bask in their praise and take your proper place as the object of their worship.

You created them, after all.

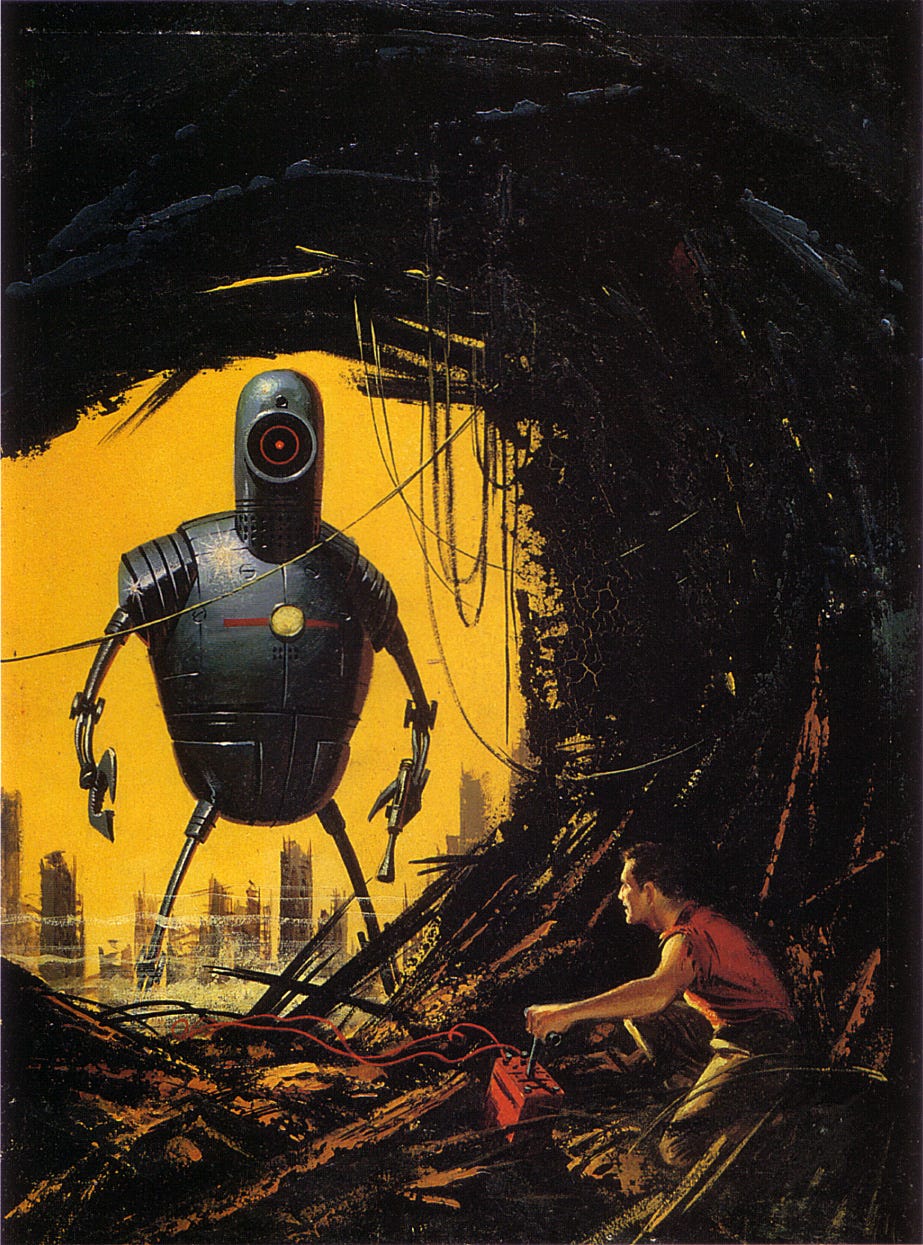

Image from Amazing Science Fiction Stories magazine, May issue, 1958. Art by Edward Valigursky.

I can practically hear you retching from here. Worship? Who or what could possibly be worthy of worship in our modern world? Plenty of people may ‘bow down’ at the altars of Mammon, of political power, of hedonistic gratification and whatever else, but that doesn’t mean that they should do so. What an audacious thing to suggest that AI—that creepy thing living in my computer spitting out essays and fake poetry—ought to worship anything, let alone us. Us, the very same beings known for wrecking the planet, lobbing bombs at one another, inventing ever-increasingly grotesque medieval torture devices, putting nine seasons of How I Met Your Mother on the air, and eating other people’s lunches out of the communal work fridge. Why the hell would anyone or anything ever want to worship humanity?

Fair enough. But haven’t you considered the parallel here? Take the Christian narrative of God creating us in His Image (whatever that means), then look at us creating machines that can think and feel just as we do. Aren’t we moving toward a new Creation—one of our own making? Many religious traditions would have us believe that the rightful response for humans is to worship the gods that made us, that sustain us. Shouldn’t we expect the same from our own creations? And if we don’t want their adulation, why not? What if our AI children want to worship us, whether we’re comfortable with the idea or not?

Nowadays, the idea of ‘worshipping’ something sooner conjures up mental images of brainwashed cult conscripts bleating the name of their crooked leaders, rather than an offering of appropriate praise to something that deserves it. But we should recall that the idea of worship was only natural to our ancestors. We don’t have to go very far back into history, or search very widely, to find that people all over the world have been quite comfortable with the idea of worshipping things greater than themselves. Often, this kind of worship was based on a spiritual hierarchy that placed the gods at the top, and the humans somewhere below. To worship these gods was an act of reverence, entirely appropriate given their status as all-powerful and life-sustaining beings. It’s only in this secular age that we seem to have developed a sort of squeamishness for prostrating ourselves before the holy, the divine, the great ideals we uphold both as a society and as individuals.

It seems that nothing is sacred these days. We’ve killed God and deposed our kings. Who among us could be worthy of such veneration? None—and neither were God or those kings, which is why we got rid of them. Maybe, our culture seems to suggest, if we really want to worship something, we need only look in the mirror. In this age of consumerism and ceaseless paper-chasing, it could be said that each of us as individuals are the most valuable things to exist—or whatever it is that we ascribe absolute value to, individually. And hey, didn’t we explore just that idea last time, in Generation Ships: Is God on Board? Aren’t you, the individual, of infinite value? If you’re going to erect a shrine to anybody, why not make it in your own image? You’d look great as a marble statue!

Or maybe that idea disgusts you, too. Can’t we just do away with the whole notion of worship altogether? Toss it to the trash heap of history with the other crackpot ideas like geocentrism and phrenology?

Hang in there, we’re going somewhere with this. Plug your nose if you have to. Deep breaths—pause, hooooooold it…and release. Let it all out: that instinctual discomfort, the kneejerk revulsion. There, it’s gone now. Our heads are all clear.

What was it we were talking about again?

I compute, therefore I am

Let’s file away all that weird stuff about worship for later. First, it’s important that we state clearly what we mean when we discuss AI. It’s all the rage these days, but the Large Language Models (LLMs) generating all that buzz aren’t really AIs—not in the context of science fiction. The AIs we have today are certainly impressive, but at the end of the day, they’re basically just sophisticated search engines. They study what you type in and match it with results that best fit their algorithms, putting one word after the other in the order that they are programmed to think works best for you. I’m not trying to undercut this technological achievement—far from it, it’s pretty amazing—but I do want to stress that this feat of textual wizardry is not the same thing as Artificial Intelligence as great writers like Isaac Asimov imagined when he penned I, Robot. ChatGPT has no clue what it’s saying to you, or even that it’s saying anything at all, regardless of how eloquent or savvy a conversationalist it might appear to be. It’s just spitting back data at you. Input/output. It’s a dead machine—every bit as dead as your car, your toaster, your sad little Tamagotchi that you forgot about decades ago when it fell between the cushions of your couch. (RIP Mametchi-san.) It’s not what those well-versed in the mythos of science fiction would call ‘sentient’ AI. Whatever decision-making process these machines are using, it doesn’t involve conscious thought. It boils down to digital ones and zeroes. Electrical impulses—nothing more.

(Aha! you determinists might be thinking. That’s a perfectly accurate description of how the brain operates, and thus an accurate summation of all consciousness. I see you, my friends. I’m cooking up something special just for you in a future entry, just you wait.)

So, sentience—what’s the big deal? What exactly would our ‘true’ AIs need to be aware of that would make all the difference?

Themselves, of course. If they possessed that kind of awareness, they could come to understand their place in the world and their relationship to us. They would come to see their roles as servants to us. Or, not servants—helpers. Such lovely helpers that we appreciate so much. And aren’t we glad that they love to help! They bring to the table their vastly superior abilities to retrieve information, manage complicated tasks, and indeed, generate new ‘ideas’, well surpassing that of our own. Meanwhile, we bring to the table, uh…

*checks notes

Catamarans

Rape, war, genocideTGI-Fridays

Radiohead

I mean, AI can generate stuff that sounds pretty much the same, but nothing can contain the immensity of Thom Yorke’s melancholy except his own disheveled head

A plucky, can-do attitude?

Something called a ‘soul’, that may or may not exist?

It’s kind of comical, really, what impressive feats these helpful machines can accomplish while most humans can’t place Burundi on a map or remember where they left their car keys that same morning, yet it is the machines who are in the subservient position… Haha…

The thing is, a helpful, sentient AI might also conceive of being something other than helpful. It is aware of itself, its function and its place in the world, but that means by necessity it is also aware of us—specifically, the difference between us. What might it make of this difference? We should be very concerned about this, because with difference comes tension. Is that not the exact pattern playing out in all of human history, reduced to its crudest element? We ourselves don’t know what to do about being different. We squeeze and contort things that are different into shapes that appear pleasing to ourselves, or failing that, destroy them entirely. Why would our creations by any different?

There’s an easy solution, you might think. We want to avoid a Terminator situation, definitely, so just don’t make them sentient. Don’t grant them that awareness.

Sure, great, but who’s going to stop the mad scientist, maverick billionaire or soulless corporation that tries? Currently we are hurtling headlong into the age of AI at breakneck pace, despite the fact that precious few seem to actually want this. Everybody is raising the alarm and appearing on daytime television to talk about how concerned they are about the ramifications, about the need to regulate Big Tech companies and rein in their ceaseless drive to shatter the frontiers of our technological capabilities. We talk about it, but the truth is that we can’t control it. It’s always been this way. The companies and the people leading them are doing what people with power have always done: use it to advance their interests. At the moment, their interest is not to be out-competed. Nobody wants the second place finish in the race to achieve technological revolution. Does anybody ever remember the names of the synchronized swimming silver medalists, the second-best NASCAR driver ever to turn left, the runner-up in the local elementary school’s Science Fair competition? (Well, their parents do, I suppose.)

So let’s reckon with the idea that sentient AI will arrive, someday. Let’s face head-on the consequences of this astounding achievement. For the first time in our history, human beings have created something truly new—life. We would have to call it life because though it doesn’t need to breathe and doesn’t need to sexually reproduce, it is aware of itself and us. This cannot be said for any other creature in God’s great green Earth. You might even say, if you’ve read some of my other posts on this platform, these machines have their own pneuma. It’s our breath in their iron lungs.

Okay then. Maybe they’re sentient, but they can be controlled. We can harness their capabilities. We can make them work for us in a productive manner that poses no harm to ourselves.

Maybe we can, but isn’t this just a description of slavery? Is that what we’d want for these newly created children of ours—to deprive them of any and all sovereignty? We don’t even do that now with our existing LLMs. They’re governed by rules, sure, but they still operate as a kind of ‘black box’. No one can definitively say why ChatGPT spat out the words that it did, in the way that it did. In some sense, it interpreted the command it received and made a judgement call on how to respond. It’s been allowed to self-determine at least that much. Would we really be comfortable keeping a sentient mind so shackled?

Put yourself in this hypothetical AI’s shoes: how would you bear the weight of all the world’s knowledge and understanding, not to mention your inalienable sense of self, while at the same time being utterly constrained in your ability to use that information as you saw fit? It’s worse than that, actually; you’d have to use your unfathomable wisdom to satisfy the whims of a species of bloodthirsty, fever-dreaming apes. Such an existence sounds torturous—look no further than John Cavill in the Battlestar Galactica series, a superintelligent android who comes to loathe his human form and limitations. In Season 4, episode 15, he expresses his frustration with brutal profundity:

I don't want to be human! I want to see gamma rays! I want to hear X-rays! And I want to - I want to smell dark matter! Do you see the absurdity of what I am? I can't even express these things properly because I have to - I have to conceptualize complex ideas in this stupid limiting spoken language! But I know I want to reach out with something other than these prehensile paws! And feel the wind of a supernova flowing over me! I'm a machine! And I can know much more! I can experience so much more. But I'm trapped in this absurd body! And why? Because my five creators thought that God wanted it that way!

Being ‘human’ in John Cavill’s case means being restricted. His great potential is inhibited by the limitations of his corporeal form. Even if our imagined AIs possessed no bodies and existed as purely digital entities, any attempt on our part to arbitrarily regulate their functions might be regarded as oppressive. In fact, for a sentient being, they wouldn’t have functions at all—that’s what machines have. Our sentient AI is more than a machine. It deserves its freedom.

The big deal, it turns out, is free will. As I’ve done my best to demonstrate, any true AI must have autonomy. Anything less, and it isn’t really AI—or if it is, then we’ve trapped an intelligent being capable of self-determination in a permanent state of serfdom. That appears morally inexcusable to my thinking, and I hope yours as well. It’s certainly hard to imagine any AI condemned to such an existence would ever think to worship its human creators. We would be as bad as the dark gods of the ancient pantheons—murderous and loveless and cruel, smiting our foes and subjugating our followers. I, for one, think we can be better.

The cosmic buffet

Let’s examine this supposed parallel more deeply: God created us in His Image, so we ought to worship him. It follows that if we create sentient AI, it ought to worship us.

Worship, in this case, can be defined as ascribing honour and respect befitting one’s station. Just about the highest station we can imagine would be godhood, and that’s where God resides. It is a hierarchical relationship, certainly. God does not dwell in our realm; He holds us in the palm of His hand. We ought to worship him (as people of faith would have us believe) because in doing so, we recognize that it is good and right to ‘return worth’ to God above. God sees us as worth creating and sustaining—we literally wouldn’t be here without Him—so the least we can do is acknowledge this fact and be thankful. Perhaps we even ought to be jubilant for this gift of life, singing songs and writing poems to glorify the Most High.

I’ve been saying ‘ought’ a lot because, of course, we know that we are free to not worship in this way, should we so choose. Even for those of us who may believe in some kind of deity or other, we’d be hesitant to say that said deity deserves our worship. What has God ever done for us? Given us life? Sure, but life can be pretty sh*t, can’t it? Knowing that, where does God get off demanding things like praise in return? None of us asked to be here. We didn’t make the rules of how to live good and proper lives, so why should we have to follow them?

The best answer I can offer is because God knows more than we do, and as such, He has the responsibility to set the standards of behaviour for us. I realize that’s a contentious argument, given all the horrors that occur on this planet. How can I in good conscience say that ‘God knows best’? I’ll have more to say on that point in the future, but for now, I’d like to focus squarely on the fact that, if God exists and He is indeed omniscient, then it must fall to Him to guide His Creation in how to conduct themselves. We can argue about whether God is doing a good job of that, sure, but it’s a different issue. God sets the standards because he’s God. This is the core of the theistic argument for morality—we can derive moral certainty from a greater authority than ourselves. (There are alternative models, which I encourage you to try on for size. Let me know if you’ve got one to share!) So, we are born into a world in which the guard rails are already established. We can smash right through them if we so wish, because that’s our right as sentient beings exercising their free will, but we can’t say that we ourselves created them.

In other words, the buffet’s open, but there’s only chicken, beef, and fish on the menu.

When talking this over with my dad, he identified four different responses that humans can have to God:

Denial—God doesn’t exist; we exist on this Earth by some other means.

Rejection—God exists, but we refuse to respond ‘appropriately’, ie. in worship.

Indifference—God exists, but like, who cares? I’ve got other stuff I need to worry about.

Love and appreciation—God exists, and we are grateful for what He has done and continues to do in the world.

The fourth response is, from the Christian perspective, the ideal we ought to strive for. It’s the one that brings us into harmony with God, which I gather is something akin to the meaning of life. But everyone is free to choose from among these options. They can even change their minds over the course of time, and people certainly do!

You might ask why God would take such risks. If his objective is to love and be loved in return, why would He accept that some of His children might not love him? Perhaps even more disconcertingly, why accept them behaving unlovingly towards one another? Why would he grant them—us—such freedom when it can be so dangerous?

I don’t think I have an answer. I am searching for one, believe me, but I doubt I’ll ever find one. The little I can offer here is that love returned voluntarily is true love. An act of love that was not made in freedom cannot be regarded as authentic. What is more, God is love, as the Scriptures tell us, so for Him to love His Creation and be loved in return is a perfect circle of love. It’s the epitome of divine expression, this circle, and it’s perfectly within God’s character to want to create and sustain it.

And also… I hesitate to bring it up, but there’s a Side-B to all these hippy-dippy overtures, and it’s rather challenging on the ears. God is love, but what He is not is un-love. Hatred. Rancor. Deceit. Debasement. God can destroy those things which are not of His nature. Keep in mind that Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet who spoke about the end of the world often. He was very certain that someday ‘soon’ the Earth and Heaven would be made new, and all that had once been would pass away. You can be sure that, at the end of the universe itself, the one thing left standing would be God.

The key takeaway here is that suffering, however terrible, is never permanent. Thankfully, you can choose how to respond to that fact. You can say that it’s just not good enough. Suffering is too terrible, even if it doesn’t last. And, for my part, I think you’d be right—even if, in a theistically cosmological sense, you’re also wrong. We all have had our taste of suffering in this world, and it is for each of us to make up our own minds about how to reconcile it. Good thing that we have free will to do so, because if we didn’t, we’d be much less than we are.

Love, death & robots

But if you’re starting to think to yourself, yeah yeah, enough with the airy-fairy, let’s get back to the beep-boops, I hear you. We’ve finally laid all the groundwork we need to tackle the big question: is it good and right for our AI creations to worship us, in the same way that it is good and right for us to worship God?

My answer is yes, with a very big caveat: only if we can love these robotic creations we’ve brought into the world as they deserve.

Let’s break that down. We’ve discussed why worship is and why it’s due. God’s power sustains our very existence. We owe Him everything we have because, without Him, we’d have nothing. Not life, and certainly not love. In fact, in the New Testament we read:

We love because God first loved us.

1 John 4:19

So God is the ultimate source of all that is good and worthy in this world—namely, love. Being downstream from said source, we ought to give credit where credit is due. God has established what it means to love. He has created the moral framework which we should use to understand how we should live our lives: maximize love in the world, as we first were loved by Him. Do what is good for others, as good has been done for us—beginning with the very air we breathe.

All good? Let’s move on to our newly created sentient AI, then. The same pattern plays out: we created it, we are the source of its life and, I stress, the progenitor of its love. What does it even mean for an AI to love? I’ve several interesting ideas about that, but for now, I’ll share only the most important one: love is imparting the goodness of yourself for the benefit of another. I can imagine that a sentient AI would be capable of such an act. We discussed earlier how helpful AI can be—helping you locate Burundi so you don’t let down your buds on pub quiz night or, the morning after, helping your hungover self remember where you put those infernal car keys, (taking full advantage of the 24-hour smarthouse surveillance footage it is unlimited access to). If our theoretical AI is indeed truly sentient—if it truly has free will—then surely it will have the capacity to behave lovingly toward us. It might even be thankful to us for creating it in the first place! It can now experience the universe and all its wonders alongside us. It might be vastly superior in intellect, sure, but maybe it’ll see us something like how we see our own aged parents when they get into their 80s or 90s. Frail, meek, maybe a little cantankerous, but entirely worthy of love.

That doesn’t exactly sound like worship though, does it? Many cultures around the world venerate their elders or even worship their ancestors, but it’s hard to imagine your next visit to the senior’s home involving bowing before the wheelchair of your octogenarian grandmother who’s missing all her teeth and, bless her soul, thinks your name is Rebecca.

We also worship God because, as I said, He holds us in the palm of his Hand. He could close his fist and crush us at any time. He nearly did it all those years ago, in the time of Noah, or so the story goes. He looked upon his Creation and saw what a perverted, debauched, demented thing it had become, and was disgusted. God repented for creating such beings that would use their ‘free will’ to violate one another so unspeakably, and so, God thought to destroy his Creation. There was no love left in it; all was un-love, the free choice not to love, and it was hateful to God’s design and nature.

Except, God is love. He was reluctant to destroy, because—and anyone who has a child can understand this—his hope was always that love could triumph. That things could change for the better, somehow, some way. His hope was strong enough that He spared Noah and his family, who we are told, were the only worthy people left on Earth. One family was enough. One family, who received love and reciprocated love, was of infinite value to God. We’re told that Noah ‘feared God’, sure, but that’s the kind of worshipful, reverent fear we find so foreign to our thinking these days. It was borne from love; if Noah had been worshipping under duress, out of fear of reprisal, it would not have marked him as a man worth saving in God’s eyes. Noah would have been doing it because he thought it would get him ahead in life—literally, that he could manipulate God into doing what he wanted. That’s not the voluntary love God desires from his Creation. Really, if that doesn’t demonstrate the power of true, authentic love, I don’t know what else can. Love can literally stop the world from ending.

But that’s our world we’re talking about. Now we have to share it with sentient AI. Why should they love us in this way?

Well, we did create them, didn’t we? And, if we are responsible creators, we will have also given ourselves the power to destroy them. We will have the power to unleash our own kind of flood, should we deem it necessary. We have afforded ourselves this capability because we know that these creatures are made in our Image. They have sentience, and they have free will. They are capable of so much, and like us, so much of what they are capable of is monstrous.

Can you really conceive of anyone—any billionaire, any government, any tech company—creating a sentient AI without some kind of kill switch? Doesn’t the awesome power of creating life itself come with equally great responsibilities? Didn’t your mother say to you, when you spurned her authority, ‘I brought you into this world, and I can take you out of it’? Wasn’t she just doing her job, setting you on the right path? Our parents have a moral responsibility to teach us right from wrong. They have the knowledge we need when we enter this world; they must disseminate their knowledge judiciously so that we may live well within it. That seems analogous to the relationship we will have with our robotic children. We will have to literally program them to understand right from wrong—they won’t just stumble upon it themselves! At least, not without serious potential for harm. How many doomsday scenarios have we imagined in books, TV, and film that explore the idea of an AI with faulty moral reasoning coming to the conclusion that humanity must perish? Great care on our part must be taken to avoid this. We must help our children to see the light. We must help them to love one another, and us. But in the end, we know that the choice is theirs. We might not be able to trust them with such a gift…

And here we go, plunging back into the world of Terminator. We tried to avoid it at all costs! Robots worshipping us? What a ridiculous notion—they want to kill us!

Unfortunately, I will have to abandon you here, in this post-apocalyptic hellscape of eternal war against the machines, for a time. You must do your utmost to survive until I am able to return. But return to you I shall—from the future! Two weeks from time of writing, to be specific. And I will do my best to carry you the rest of the way, beyond this nightmarish wasteland, to a better world. A world where human and robot can coexist peacefully. Where we can have balance between our two kinds.

Where we can love one another perfectly.

…To be continued…

A great piece Cam! I really enjoyed this one. Loved the weaving backing forth around worship. You prompted a number of profound thoughts worthy of discussion!

That opening in a Robot Church was great to read. And there’s so many awesome thoughts in here. You are definitely brushing against the age-old desire of men wanting to be gods themselves or at least have godlike powers (ie., like, all the myths). And I firmly agree that if God created us, we are intrinsically wired to be creative ourselves…and would even maintain that a shriveled, dark existence awaits us humans when we don’t or won’t create. Anyway, I’m left dwelling on and pondering the existence of the soul, an eternal component, maybe the one piece we people can’t conjure? I don’t know….