Generation Ships: Is God on Board?

They might be our best shot at interstellar travel, but are they ethical?

Ding-dong!

You grumble as you peel yourself off the couch. Damn doorbell—this early? You weren’t expecting anyone. If it’s Jehovah’s Witnesses again, you think to yourself, this time I really will just shut the door in their faces…

You reach the door and, with a sigh, drag it open. It’s a man with a shiny smile, wearing a red polo shirt. There’s an ID card hanging from his neck. A salesman. Not much better than a Jehovah’s Witness. Worse, maybe? You’re about to mumble no thank you, have a nice day—all the while doing your best to avoid his gaze—but you’re sluggish without your morning coffee, the baby slept horrendously last night and, well, he’s got the drop on you.

Before you know it, he’s handing you a pamphlet and you’re flipping through its contents with a false, bemused grin on your face. He’s babbling about future-proofing civilization, contingency planning for nuclear holocaust, the unviability of subterranean fallout shelters and other inane things that he’s obviously memorized from a script. But he appears earnest, you’ll have to give him that, and he just won’t stop talking long enough for you to force a grin and intone, with feeling: I am not interested in buying anything from you today.

He blinks at you in surprise. Oh, look at that—you did manage to say it aloud, only it came out much harsher than you’d intended. All of a sudden you feel terrible.

“But,” he says, his shoulders drooping, “it’s only a matter of time before it all comes to an end. You’ve seen the news, haven’t you? Don’t you want your family to have a future?”

Well, of course you do. Don’t you?

He takes your silence as an opportunity.

“For the low, low price of seventy thousand universal credits—which can be split into monthly payments, if you wish,” he says, leaning close enough to tap the numbers glittering on the paper in your hands, “you can reserve a space for yourself and your children aboard one of our Arks. You’ll never have to fear the destruction of Earth by asteroid strike, or the total collapse of the ecological system, or the outbreak of a deadly pathogen, or the impending thermonuclear apocalypse. You and your loved ones can begin new lives in Alpha Centauri, continuing the human story—as well as your own, I might add!—in security and a safety. And, should you wish to upgrade your package, we have an array of different options available to you to help make the journey more comfortable. It is going to take over a century and a half, after all…”

You’re not quite sure how it happens, but the man keeps talking, you keep nodding your head and murmuring about how concerned you are about the sorry state of affairs in the world today, and then, inexplicably, you’re looking down at your own hand, surprised to find the man’s red pen clasped between your trembling fingers. A clipboard slides into view. There is a form on it, with a space for your signature. It’s so empty. It needs to be filled. It’s life or death.

All it takes it a few strokes. When you’re finished, the weight doesn’t lift off your chest. You stare blankly at your name—your children’s names, your children’s children’s names, your children’s children’s children’s names—printed in blood on the page.

“Well,” the man says, beaming now. Whether its because he’s relieved that you’ve made the ‘right’ choice, or because he’s made his commission, you can’t tell. “Thank you very much for your time. An agent will contact you soon regarding the details of your trip. In the meantime, you’d better get packing!”

You hear hushed voices behind you, somewhere inside the house. The kids are wondering who you’re talking to, what’s taking so long.

Have you doomed them, or saved them?

One thing is certain: you won’t live long enough to find out.

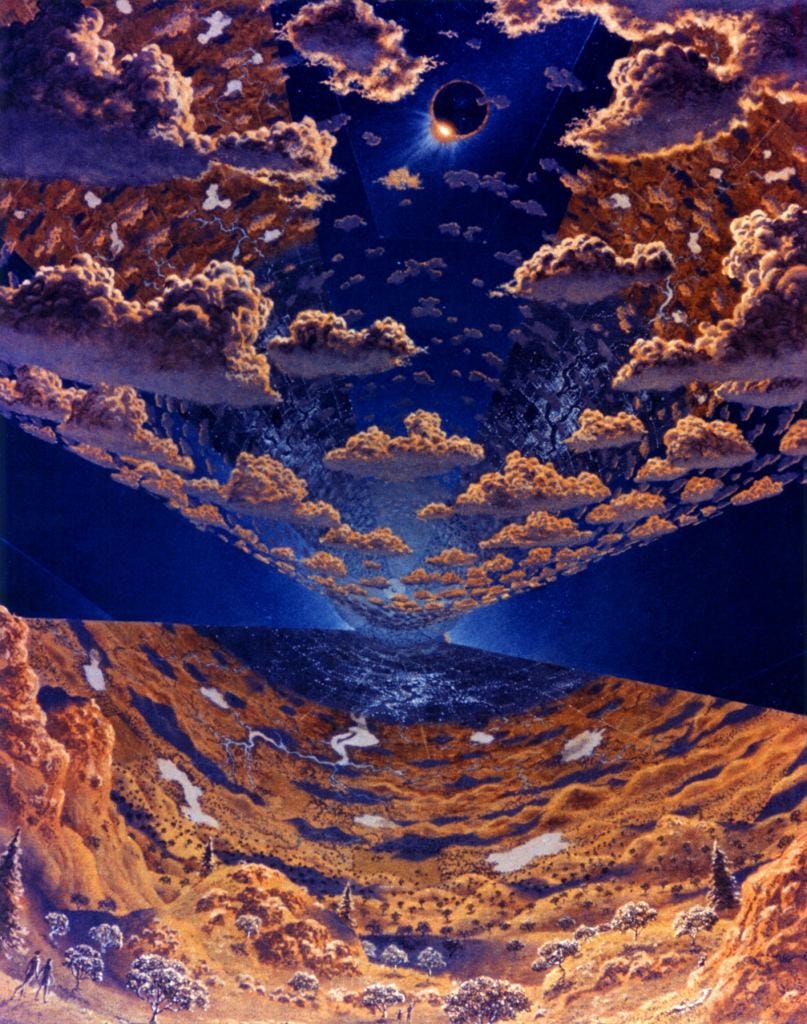

The interior of a generation ship. Credit to Don Davis/NASA

Ah, welcome aboard, traveller! I see that you’re interesting in continuing this little excursion into the unknown. But first, just what is a generation ship, exactly? Are they even feasible as a means of reaching distant worlds? Do the benefits outweigh the risks? What would God think about entire human societies sustaining themselves in perpetuity aboard these strange theoretical crafts?

All in good time. First, I’d like to mention that this essay builds upon the ideas discussed in my previous entry, A Divine Mandate to Conquer the Stars? I’d encourage you to start by reading that, if you haven’t already. But, if you’re pressed for time (or just not that interested) never fear—we’ll explore each of the above questions with rigor and zeal.

Blast off in 3…

2…

1…

‘It’s a long way to Tipperary…’

For those who may be unfamiliar, ‘generation ships’ are a science fiction concept that have been used in many works over the centuries—yes, centuries! The earliest story featuring a ‘vessel large enough to contain the necessaries of life’ appears to be John Munro’s A Trip to Venus, published in 1897. There he envisioned a massive craft capable to delivering human passengers—potentially many generations of them—to the planet Venus, well before anybody imagined the shuttles that would deliver humans to the Moon as part of the Apollo program. In essence, a generation ship is any kind of spaceworthy craft capable of crossing the incomprehensible distances between stars whilst sustaining human life indefinitely. That last part is tricky because the distances in question are so vast (or space travel is so slow, if you want to look at it that way) that such a voyage would outlast the voyagers themselves. To see the journey through, there would need to be a supply of new people to take the places of those who came before—ergo, a ‘generation’ ship. Munro imagined that his kind of ship might even survive in the depths of space for millions of years, so long as it had access to enough fuel.

But there is a dark side to all of this. While Munro’s story focuses on the excitement and wonder of travelling to our nearest planetary neighbour, he does touch upon the anxiety that the travelers might feel were they to venture further into space, far beyond the solar system. He plants the idea that the deeper one sojourns into the unknown, the less they might feel connected to the place they came from—especially if there is no hope of returning. This raises profound questions for ourselves, as we contemplate the potential reality of travelling to stars beyond our own, using the technology we have (more on this in a moment): how the human beings aboard a generation ship change over such lengthy periods of time? How the descendants of those pioneering voyagers view their ancestors’ decision to jettison them off to some strange world, relegating the purpose of their entire existence to being nothing more than a link in the generational chain? Maybe they’re not so thrilled about being confined to a flying tin can for their whole lives; maybe they’re not enthused about the ‘need to breed’ mantra chanted by the powers-that-be, so intent upon keeping the mission alive. Not everybody wants to be a parent, you know—it’s hard work!

Before we go further, I think a word on the feasibility of this mode of interstellar travel is warranted. Generation ships are science fiction for now, but they may not always be—and I don’t know about you, but I like to be prepared. With the technology we possess today, building a generation ship capable of reaching distant stars is not out of the question. It would be immensely expensive and immensely impractical, sure, but not impossible.

Let’s use our nearest stellar neighbour as a working model: Alpha Centauri. This triple star system lies a little over four lightyears away from ourselves. It is confirmed to have at least one potentially habitable planet, possibly more. Now, let’s suppose that nuclear war or some other calamitous disaster breaks out here on Earth, and a certain group of humans decide that the best way to preserve the human race is to get themselves off-world. (But who chooses who stays and who goes? I hear you ask. Excellent question! We’ll get to that.) These people pack themselves onto a generation ship—or perhaps a fleet of them—and head off to sunny Proxima Centauri, the particular star which our target planet orbits.

Depending on the technology utilized, it will take them anywhere between 145 to 6,300 years to reach their final destination. That’s a rather dramatic gap, isn’t it? Here’s a quick breakdown explaining it, or if you’d prefer, a link to the original source:

If the generation ship travels at the speed of the fastest known manmade object ever launched (the Parker Solar Probe, flying at nearly 700,000 km/hour) it will take the ship 6,300 years to reach Proxima b (the Earth-like planet in question). This is about the same as the entire span of recorded human history—a phenomenally long time in human terms, though not really in cosmic ones. Of course, it is very difficult to imagine how such a mission would be viable. How could we possibly account for the evolution/transformation of human cultures and sensibilities over the course of that period, considering how much we have changed over the past six-plus millennia?

If the generation ship uses an acceleration strategy—such as continually detonating nuclear explosions at the rear of the vessel—the ship could theoretically travel at speeds up to about 10% lightspeed (but, to be conservative, and because the source from which I gathered this information thinks it best, we’ll stick with 3%, or approximately 32,377,000 km/h). This would greatly reduce the total travel time to about a century and a half; again, well beyond a single human lifespan, but not so long a period that it seems insurmountable. That’s about only about one more generation than the number between ourselves and our friend John Munro! The late 1800s were certainly a different time from now, but perhaps not so different that we can’t imagine how we got from there to here, developmentally speaking.

So, for the purpose of this exercise, we will go ahead with the second model (albeit the more scientifically tenuous one). Our group of intrepid—or just plain rich—human beings load themselves up onto their generation ship and launch off into space. Those aboard know that they will never see the Earth again, just as they will never see the their new homeworld. But they have hope. Their children will have children, and those children will have children, and those children will have more children still. Eventually, their progeny will inherit the New Earth, allowing life and civilization to continue. It will be the single greatest achievement in the history of mankind.

Won’t it?

Lessons from the first ark

You might have already thought about a certain Biblical story that parallels this idea. Could we say that Noah’s Ark was the first generation ship? Let’s examine that notion together, because if the comparison holds, it would suggest that we’re on the right track with packing human beings into tight spaces and launching them off without a clear ‘stop the ride, I want to get off’ option. If God did it once before, it seems reasonable to assume it would be worth doing again (working from the viewpoint that God is in fact good, and the things He does in the world are good. A contentious point, no doubt, especially when we consider the flood story! Still, I ask that you hold to this view for the time being, for the sake of argument.)

Allow me to briefly recount the story, for any who might be unfamiliar: in ancient times, God looks down in displeasure upon his Creation, witnessing the egregious evils that humanity inflicts upon itself, and indeed, appears to revel in. God ‘repents’ of his decision to create man in His image and declares that He will wipe them from the face of the Earth. However, there is one individual who finds favor in the Lord’s eyes: Noah, a good and faithful man. God tells Noah to construct an ark (read: generation ship) that will preserve him and his family from the coming flood that promises to destroy the many peoples of Earth. Noah does so dutifully, gathering together his loved ones as well as two of every kind of animal, male and female, and boards his craft. The rains come, the world is drowned, and all perish save for those aboard the ark.

In the end, the rains relent and the flood waters recede. The ark runs aground atop a mountain and Noah is able to disembark safely with his family. They reemerge into the world, itself newly cleansed and recreated, and they begin to rebuild. The human story continues with God’s everlasting promise that no such calamity will ever befall His children again—a calamity of His making, I should specify. That distinction will be important later.

What can we take from this story and apply to our current situation, then? In the face of inevitable, world-sundering disaster, is it not correct that people respond by fleeing to another world, as Noah did? Keep in mind that we are looking at the Genesis account as a story—albeit, one weighted with meaning. It’s immaterial whether the story is ‘true’ or not; we can still draw conclusions about the moral justification of our own generation ship by comparing it to the first one ever to set sail. Why? Simple: stories can point us towards higher truths. To put it crudely, you don’t need to jump off a bridge to know for a fact that you will drown in the river below. A story about some other poor fool who tried it will tell you all you need to know. It doesn’t even matter if the fool actually jumped or not! What matters it the truth it points to: fools, bridges and rivers are a dangerous combination, best avoided. You can derive truth from a story, even if the story itself isn’t true.

So, then—the lessons that we might draw from Noah’s story. Off we go!

God chose Noah

I won’t pretend to have a perfect theodicy that will satisfy the skeptics among us—I don’t think anyone does. How God can justify sparing one soul while countless others are destroyed? Did the other people living in Noah’s day deserve destruction? The Biblical account seems to suggest so. But how bad could they be, really? And doesn’t God bear some responsibility for their ‘badness’, as it were, since He created them? Was God’s decision-making process fallible?

Excellent questions all, but in my view, they’re marginalia. You might well argue that God showed poor judgement in ‘choosing’ Noah, and no one else. Fair enough, but it doesn’t alter the fact that, if the species were to survive, someone needed to build a boat. A choice had to be made, somehow!

But who, who is chosen? I hear you cry. On what basis? How can this ‘choosing’ possibly be construed as good or fair in any sense?

Gosh, you’re really on fire with these daggering lines of inquiry. I encourage you to seek answers! All I can say is that, based on this story, the act of ‘choosing’ does not appear to be morally wrong in itself. Whatever the mechanism we humans use to decide who stays and who goes on this interstellar journey, while it would be well and right to criticize the manner of the choosing—and likely also the people doing said choosing—the choosing in and of itself is above reproach. In such a scenario, we simply couldn’t save everyone. A decision would need to be made. I’m sure the alternative—absolute destruction of the entire human race for reason of inaction—would not be superior.

But I recognize that I might be falling afoul of the ‘something is better than nothing’ supposition, as some of you may be itching to point out. You’ve got me there. I’ll save a final thought on this point as a closing remark…

Noah’s family didn’t get to choose

We haven’t mentioned them explicitly before now, but Noah does bring his wife and sons aboard the ark, along with their wives. God never speaks to them—they’re pulled into the story by Noah, the family patriarch. Were they deprived of agency, then? Does the question even matter, if to disobey meant a watery grave?

A criticism that may be levelled at the idea of generation ships is just this: all future generations would be consigned to a miserable existence aboard one of these crafts, with no hope of ever escaping. There’s no question that life on a generations ship would be difficult in ways that life on Earth is not. Frugality would have to be the governing principle for those who called it home. Space would be limited, food would be limited, potential mating partners would be limited; life would be defined by the desperate need to conserve resources. It is easy to imagine that the personal freedoms of our travelers would be greatly curtailed as well. How many artists would a generation ship need to function, versus how many engineers? What would the ratio of impressionistic painters to trained astrophysicists be? Would marriage or procreation be compulsory, since the entire point of the voyage is to produce a generation that will replace the one that came before?

The likely answer to these questions would be not many, about 1:100, and in all probability, yes. So, given the repressive strictures that life on a generation ship would require, is it not unethical to doom future generations to this mode of existence? Noah’s sons built the boat while their dad got to preach—shouldn’t they have had some say in how it all ought to play out?

Consider this: you’re living on a generation ship right now. It’s called Earth. It’s sailing through space at 828,000 km/h, twirling around the Sun, spinning around the center of the Galaxy. You didn’t choose to be here—your parents did that. You might feel as if you’ve chosen the path that you’ve taken through life, but if you adopt a zoomed out view, are you not living out the same pattern as all generations before you? You’ve likely followed most of the same landmarks: childhood joys, first loves, parental conflicts, striking out on your own, stumbling and finding yourself, successes and failures, discovering a sense of identity, and striving for happiness, fulfillment and purpose. In that sense, you’re carrying the same torch that your ancestors once did. You’ve been born into a story much greater than yourself, and though you author your own small part within it, you do not author the whole.

Or consider this, if you’re still not convinced: don’t parents have the right to choose what’s best for their children? The decisions they make might be imperfect, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s their prerogative to choose. If I think my family will be better off immigrating to a new country, am I not fully justified in bringing my children along with me, though they have no say in the matter? It certainly won’t be easy for them. Their lives might end up being harder in some ways than at home. They’ll lose friends, have to navigate an unfamiliar culture, perhaps have to learn a new language. But the family goal we are aiming for justifies this difficulty. We are aiming to improve our lives over time, as a whole, not as individuals. The decision to move is greater than any one of us.

So, in sum, I think it’s hard to argue that any one person has some inalienable right to ‘choose’ the manner of their own existence. As hard as life aboard a generation ship may be, it would not be unethical to bring children into such a life. We needn’t be theoretical about this point; people raise families in unbearable conditions right here on Earth. Starvation, famine, disease, war—these have never been enough to deter people from starting families, else we would not be here. It is simply the reality of human life on Earth that we struggle and suffer. Some of us suffer more than others, yes, but suffering is everywhere and touches everything. To argue that bringing children into this kind of suffering is akin to saying ‘it would be better to have not been born than to have suffered so,’ which strikes me as misanthropic in the extreme.

And yet, I am reminded of Job, who uttered those same words as he suffered… Perhaps all we can really say is that, if there is something worth living for, then it is worth bearing the suffering of living.

There’s something about humanity worth preserving

Is it love? Family? The innocence of children? I’m not sure I can say. All the Bible appears to be telling us is that Noah was righteous in the eyes of God—a good man, to put it in simple terms—and so it it was worth keeping him alive. We know this intrinsically; human life is precious, and the moral virtues of kindness, faithfulness, trustworthiness ennoble us as a species. We’re the only beings on Earth capable of truly ‘loving’ one another. We can love another in that transcendent, self-denying way that goes far beyond simple biochemistry or biological programming. Thus, we can extrapolate upon this simple truth: were our kind to be threatened with extinction, to keep even a few of us alive—to keep love alive—would be a worthwhile endeavor, indeed.

How could someone possibly object to this? Perhaps weighing the cost of preserving a small fraction of humanity leaves us ill-at-ease. As with Noah, the vast, vast majority of human beings living upon the Earth will not be spared our (theoretical, hopefully) catastrophe. How easy it is for the survivors to justify their survival to themselves, cooped up safely in their arks—they didn’t have to face the rains or the asteroid or the bombs, knowing they would never see another sunrise! Can we imagine that the doomed would comfort themselves by saying, ‘at least the species to which I belong will be preserved, though I and those I love may be reduced to dust and ash’? The terrible injustice of saving the few over the many is self-evident; how could we ever say in good conscience that one life is more valuable than another, let alone a few lives more valuable than a multitude?

And so, we come back to that issue from lesson one. I have a rather bleak thought to share, so brace yourself: how can we be certain that preserving the human species truly is justifiable when we know that it will come at such an extraordinary cost? That might seem like a ridiculous notion, but for the reasons stated above, it should at least give us pause to think of the suffering that this embarkation will wreak, not just upon the unfortunate souls left behind to die, but all those descendant of the souls ‘lucky’ enough to secure a spot on our generation ship. Who among us could push the big red LAUNCH button in good conscience?

Well, is doing something better than doing nothing? Our instinct might tell us so. But let’s also remind ourselves that, in the Christian view, this life is not all there is. If we trade our souls to save our lives, what have we really gained, spiritually speaking? In the Bible it is quite clear that the world is bound to end in fiery ways—quite literally, when you consider that the Sun will one day go supernova—and that life will continue anew beyond this world. We cannot escape our inevitable demise on this plane of existence. Memento mori, dear friends, for the universe and ourselves. Knowing this—knowing that God does not guarantee the ‘salvation’ of the human race forever, and certainly not from itself—should perhaps be reason enough for us to wonder if adopting an attitude of ‘survival at all costs’ is ever morally defensible. We may add years, centuries, even millennia to the longevity of the human genome, but the same question will always haunt us: was it worth the sacrifice?

All aboard the Love Train!

Thus far, our experiment has only imagined that humans might want to venture out into space to save ourselves from certain annihilation, self-inflicted or otherwise. Our survival instincts are strong, after all, and we put a premium on the sanctity of human life. We’ve assumed that it would be a good thing for us to endeavor to continue the species somewhere far from home—though we can’t claim to be divinely destined for the stars, as discussed in my previous essay. But as we’ve seen, such a rationale still leaves us with a sense of moral squeamishness. We know in our heads that these drastic actions are good and right, yet still our hearts break as we see them through. We understand, profoundly, the value of a human soul. Any appraiser worth their salt will tell you it’s infinite! A single soul is an entire universe unto itself. To lose one an immeasurable devastation because it can never be replaced.

And this is a fantastic thing about infinity: it’s scalable. Or, actually, it’s not scalable at all. It’s hard to explain—go with me on this.

Imagine you have an infinite number of apples. That’s a lot of apples! You’ll certainly never go hungry, though you may sicken of seeing them in your lunchbox.

Now imagine that your neighbour has an infinite number of apples, as well as an infinite number of oranges. They must be better off, you’d assume, but don’t feel envious just yet! If you count carefully, you’ll find that your single trove of apples measures exactly as large as your neighbour’s apples and oranges combined.

On the face of it, that statement appears nonsensical. Of course two is greater than one. However, the concept of infinity more or less breaks our fundamental understandings of the universe. (Perhaps that’s the mark of the divine in us—that we can conceive of infinity, though we can never truly grasp it.) Even one set of infinity, be it apples or an indivisible human soul, is equally as vast as a supposed ‘greater’ set of infinities. In other words, you have just as many apples as your neighbour has apples and oranges put together, though that confounds standard logic. The same hold true if your neighbour has an infinite number of infinities! You name it: apples, oranges, pears, pineapples, plums, lemons, limes, grapes, squash, pomegranates, asparagus, tomatoes, potatoes, beans, lentils, starfruit, grapefruit, watermelons, dragonfruit, artichokes, radishes, horseradishes, bok choi, egglants, broccoli, blueberries, raspberries—every kind of berry, really—cucumbers, carrots, parsnips, peppers, cabbages, corn, cauliflower, onions, spinach, brussels sprouts, beets, leeks, turnips, rhubarb, zucchinis…

The list goes on, ad infinitum. Your infinity is worth every bit of theirs, and then some.

But I digress. What other reasons might there be to venture out to the stars, if not for survival? Are there options available where we don’t have to dirty our hands? When my dad and I put our heads together this past week, we were able to come up with just one: love.

It’s same reason that you and I are here having this conversation. Noah survived his flood and repopulated the Earth (if you want to take a literalist stance on the story) because he loved God, and we would assume, his fellow man. This is what made him ‘righteous’ in the Lord’s eyes. Yes, typically we think of being righteous as following the rules—very Old Testament sort of word, ‘righteousness’—but all it truly means is to do things the right way, as they ought to be done. We know that the great command of Christians is to love God and their neighbours as themselves. Even Noah did a fair amount of neighbour-loving, trying in earnest to warn his countrymen of the coming storm.

So, suppose we adopt this as our ethos for travelling to Alpha Centauri and beyond. Suppose we take our divine mandate to be the sharing of love across the universe, rather than ‘conquering’ the natural world because it’s there and it has resources and we have the technology to extract it. There wouldn’t be much point if the universe is indeed a dead and empty place, but good news! It’s likely teeming with life (that, for some reason, we’ve yet to discover). It’s probable that we will encounter some manner of intelligent life elsewhere in the cosmos, so why wouldn’t we want to pay a visit? Perhaps this is just as God imagined all along; in time, we would climb to the stars to share what He has done in our hearts with these new neighbours we’ve found. No doubt we’d still get it wrong in a million ways—all of the moral issues I outlined with travelling aboard generation ships would still exist—but at least we would know that our reason for journeying in the first place was legitimate. Also, if we weren’t worried about our planet being blown up one way or another, we were just doing it for the love of it, maybe we might not have to resort to emergency measures and could actually figure out a way to build and crew these ships in an entirely ethical manner. We can dream, can’t we?

Out with the new, in with the old

Finally, we have the driving philosophy for our generation ship project. We will travel to the stars aboard generation ships not because we must, but because we wish to share that which is most precious: our love for one another, and for all God's creatures. Let’s get building!

We’ll have to make some changes, though. Sure, the designs and the dimensions will need work—we’ve got our best people on that, don’t you worry—but it’s ourselves that we need to take a look at. How are we going to handle this journey? The limitations upon our free will that such an endeavor will require; the curtailing of our independence and right to self-determination? We enjoy such amazing privileges in our modern world. I daresay we’ve grown entitled to them. And why shouldn’t we be? Are human souls not immeasurably valuable, as I’ve already demonstrated? Why would we ever think it to be permissible to oppress one such beautiful soul, for the benefit of another—especially if said soul was not a willing signatory to the Alpha Centauri interstellar expedition!

Our conceptualizations of ‘free will’ and individualism are frameworks that have been centuries in the making. A chain of philosophers from Hegel to Locke to Machiavelli have explored the notion of personal independence in depth and detail, advancing our self-understandings as insular entities—universes unto ourselves—jammed up against one another and stamped into submission by the arbitrary dictums of state and social convention. We have broken free from these shackles to a large extent, and live lives where we exert a level of self-determination that the medieval peasants of old could never have dreamed of. We are the lords of our own houses. None may tell us how and when we should act, least of all some stuffy scientists calculating the ideal number of hydroponically grown sponge leaves we may eat for our dinnertime rations aboard the spacecraft conveying us to some distant planet without our consent!

But, the funny thing about conceptualizations is that they evolve. They are never static. Just as our current understanding of what it means to be an individual exercising free will has evolved out of the work of Enlightenment thinkers and the cultural/sociopolitical waves they rode, they will continue to evolve. Give it a hundred years and we might not recognize ourselves anymore as a species—and not because we’re an irradiated bunch of mutants scrounging about in a post-apocalyptic nuclear wasteland.

What I’m getting at is that the human beings who set out on these multigenerational journeys will likely adopt a different framework of conceptualization. They’ll need to—the kind of hyperindividualism we enjoy today simply isn’t sustainable in a project that fragile. To be successful in reaching their destination, they’ll need to shed some of that individuality and embrace in its place collectivity. This isn’t anything new—for most of human history people have understood themselves fundamentally as belong to groups or nations, rather than viewing their ‘self’ as the ultimate realization of their identity. A person’s identity was much more wrapped up in the welfare of the ‘whole’ than it is today. Across the globe, across cultures, people identified strongly with their kings, queens, nations and tribes. When a person’s group went to war, they went to war as an individual. They fought and died first and foremost for the whole, not the self.

I’m not saying that this kind of framework doesn’t exist anymore—only that the emphasis has shifted here in our advanced, late capitalist Western societies. But we would need to shift again if we are to see our mission succeed, away from the kind of individualism we’ve grown accustomed to if this generation ship thing is ever going to work. Ursula K. Le Guin’s novella Paradises Lost captures this truth well—the older generations fear that the younger ones, the inheritors of their great mission to reach their New Earth, have grown too comfortable with their lives aboard the craft and have lost sight of the ‘whole’; the need for their entire group people to achieve their destiny, which includes all those who have lived, who live now and who will live in the future. Personal choice is key, admittedly, as the travelers of the ship are given the option to colonize the planet when they eventually do arrive, but the gravity of this choice is made clear by nature of its permanency. The generation ship will not return after those citizens who elect to descend to the planet surface have made their choice. In the same way, the choices afforded to the travelers of our own ship would be inherently weighty—each decision affecting the welfare of the society as a whole—and would need to be approached with a keen sense of personal responsibility, counterbalancing that of personal autonomy.

And so we have arrived. We’ve covered all the bases, or so I think. I’ve brought you this far—the Ark is there in front of you, ready to embark. The engines are purring; the grav-boosters are thrumming with energy. Hundreds of faces flicker in the portholes. People alongside you cheer, cry and wave as their loved ones walk the gangplank and disappear into the bowels of the ship. This must be what the Titanic looked like from the dockside, so many years ago.

The ticket is in your hand. Are you getting on?

What a fun, mind bending mental exercise. Loved it.

Thanks!

st