Extraterrestrial Evangelism?

What are Christians supposed to do – go out there and convert them?

Not very far from here – right in your own neighbourhood, you might say – there is a frozen, desolate world that no human has ever set foot upon. It is an empty plain, eerily smooth, almost as if sculpted by an invisible potter’s hands. There is no air to breathe, no wind to stir the silence. Everything is dead and empty, save the sudden violence of a geyser bursting out showers of frigid vapour. And below the surface, buried deep underneath the brittle crust, there may just be…

Life.

I’m writing of course about Europa, one of Jupiter’s Galilean moons. It’s about the same size as our own, but unlike ours, it does not have crater marks. This world appears to be able to ‘heal’ itself, due to what may be a liquid ocean hidden beneath its surface. Scientists theorize that this ocean might be harbor some kind of biosphere – likely not very advanced beyond microbial life, but life nonetheless. Right now, a probe called the Europa Clipper is hurtling through space at 35 kilometers per second to investigate this strange place. When it eventually does (the year 2030, if everything goes to plan) we might just learn the answer to a profound question that those stargazers among us have been asking for centuries, if not millennia: are we alone in the universe?

Science would suggest that, no, we are not. Space being as vast as it is, and the chemical components required for carbon-based life being as widespread and commonplace as they are, would indicate that life should be a fairly unremarkable phenomenon in our universe. Yet despite several decades of intense searching, we’ve not discovered any sign that there might be anyone out there to meet us. We’ve sent out radio signals, and no one has responded. We’ve sent out probes and beacons, but they are out drifting in the dark, lost and friendless. If consciousness, intelligence and sentience are like opera boxes from which we look out and observe the cosmos conducting its exquisite performance, then we seem to have the best seats in the house all to ourselves.

And, perhaps it might be said that, from a religious standpoint, this strange loneliness is actually a kind of comfort. It affirms of our special place in the mix of things. We seem to be chosen, don’t we? But we’ll come to that point later.

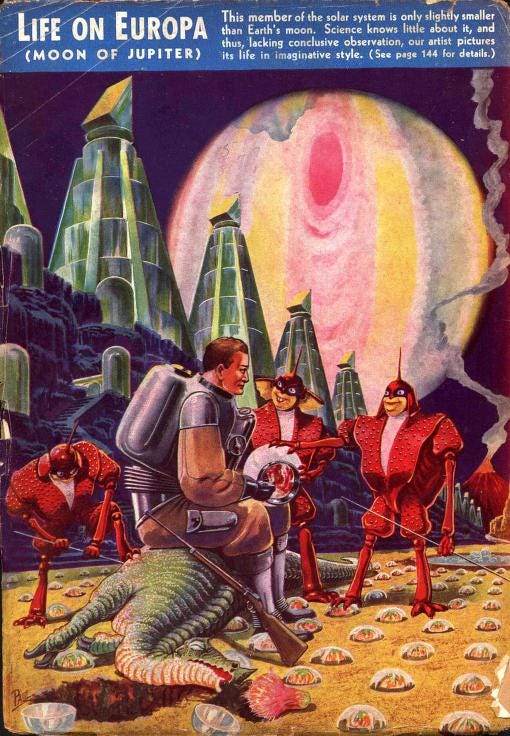

Illustration by Frank R. Paul - originally featured in Amazing Stories September 1940 issue

A strange question, revisited

There was a distinct sense of déjà vu as I booted up my computer, made the connection across the continents and saw my dad’s face pop into view. We’d kept contact in this way every Sunday for years since I’d left home. I’d grown more used to seeing a digitized representation of him than my dad himself, but that wasn’t the reason for this strange feeling; it was the question on my mind, looping back around after completing a long, long orbit.

“Hey, dad. Let’s go back to that day we talked about aliens in that Tim Horton’s by the highway. What do you think – are we supposed to go out there and convert them?”

I don’t remember how the conversation went that first time we had it over ten years ago. What I do remember is that my dad took me seriously then, just as he did now. My dad was not afraid of this question. To my mind, that’s an extraordinary thing. My dad has devoted his entire life to the church and to ministry – my mom, too. It has shaped him, his family, and now ours. He’s endured having to reconstruct his whole belief system after parting ways with the old church he’d once served – the one I’d been born into. He redefined himself and who he was as a believer, before devoting himself to ministry all over again.

What I’m saying is, in a certain sense, he had a lot to lose. Faith – or any worldview that we use to orient ourselves, for that matter – is like a tower. You start with a foundation. This is some kind of belief that you set as the cornerstone of your perception, from which you build outwards and upwards. You construct it stone by stone, higher and higher, belief by belief, experience by experience. You look out from that tower and make sense of the world that you see. But your vantage is, of course, dependent upon where you initially chose to build, and how high you choose to go. You might find that your view is obscured, or that your tower is liable to crumble and fall. It is a difficult thing to discover you’ve built upon the wrong foundation, in the wrong place.

Allow me to be more direct: my dad and I both understood that a question like the one I’d asked had the potential to knock down any Christian believer’s tower. Key to understanding one’s place in the Christian story is to grasp the special role that one has as a Child of God – a wayward, wondrously unique little soul, beloved by the Father and free to roam the Earth for His pleasure. This mantle of God’s chosen – the vessels of His spirit, the epitome of His creative work – is heavy to bear, but it is noble. It gives one clear purpose and a direction in which to move: ever closer in relationship with God.

Unless, of course, there are alien species out there who bear this mantle, too. Wouldn’t that shatter the paradigm entirely – to discover God’s secret, other family? What kind of Christian couldn’t but reevaluate their relationship with their Heavenly Father after having such a bombshell dropped on them?

But my dad leaned into this question and took it for what it was: an exploration of possibilities. We don’t know the answer. We might never. But we do know that faith ought to be tested, tried and trialed, so why not with this? In this spirit, the two of us got talking again, just like we had in that Timmies all those years ago. It was great to take another swing at it, now a little older, a little wiser, a little more in wonder at the mystery of this universe we call home, this God we call Father.

You might be thinking, hang on: microbes eking out an existence on a frozen moon somewhere doesn’t seem much like the earth-shattering alien encounters that are often depicted on the big screen or in sci-fi novels. That’s not intelligent life. A Christian reader might be thinking that, even if God made life abundant in the universe, he didn’t make anybody like us. We can still have our special relationship as children of the divine.

But it’s really just a question of time. With enough of it (and there’s plenty to go around this universe, that’s for certain) evolution can do its work. Europa might be unimpressive now, but where there are microbes, there might one day be complex aquatic organisms. And where there are complex aquatic organisms, there might one day be land-based organisms. Fast forward enough and one day there might even be big-brained, bipedal, hairy, horny, thinking and feeling beings much like ourselves.

And so, we finally come to the question at the core of all this: when we finally do meet that strange neighbour with big brains and horns and thoughts and feelings of their own, what does the Christ-believer do? What does anyone who subscribes to any kind of faith system do?

Well, we’re hardly representative, my dad and I, but here’s how we tackled it:

1. Calling all missionaries

“Whoa, whoa, whoa - missionaries? Colonizers, I think you mean.”

It’s difficult to talk about the role of the missionary in today’s world because we are so tortured over what it has looked like in the past. In the age of European colonization, brutal subjugation of non-Christian populations was justified in the name of spreading the faith. We abhor this now, rightly recognizing it as a terrible abuse of Christ’s command to ‘make disciples of all nations’, but it happened – and it happened over the course of centuries. Not enough can be said to redress the damage caused, the lives lost, the cultures and spiritualities crushed. And, to be blunt, I am not equipped to appropriately comment on the catastrophe.

Before I go further, allow me to reiterate that the goal of this piece is not to proselytize, sermonize or moralize. I certainly am not seeking to peddle colonialist conceptions of unchristian ‘savages’ in need of civilization, as if hordes of humans venturing out on holy crusades to alien planets would produce results any different to what we’ve seen here on Earth. As always, the aim is to explore this strange idea of extraterrestrial evangelism and imagine the possibilities with curiosity, humility and grace. We will tread lightly, dear reader, in full knowledge that we are limited creatures who are shaped by our experiences and perceptions and prone to getting it wrong – very, very wrong. As such, we won’t seek to do any harm, and will hold in our hearts a keen awareness of the extraordinary damage that has been done to people and cultures the world over in the name of propagating ‘Christendom’.

So, then: it seems reasonable to assume that the average Christian person’s kneejerk response to the sudden revelation of an alien species would be to evangelize them. For organized structures within the faith, this approach seems likely to be adopted as the ‘official’ position. Likely the rationale would stem from Christ’s call for his followers to spread the Gospel across the world, as I stated earlier. (The alternative, I assume, would be to ignore the aliens and make no effort to share the faith with them, but it is more difficult to imagine this approach being taken if it is self-evident that the aliens in question are our intellectual equals, and that they constitute a ‘nation’ by token of being a distinct species from ourselves.) I can foresee calls for mission-work resounding across the church; monks, youth groups and professionally trained proselytizers boarding spaceships to travel to distant planets to preach the Good News to these creatures – just as soon as anybody could figure out what their language was, or how to communicate via telepathic exchange of thought-shapes as is customary to these aliens, or if they even had a language at all.

I joke, but evangelism is a core component of how many Christians understand their responsibilities to God and their fellow humans. This is true perhaps not only for Christians, but people of other faiths as well. Virtually all human spiritualities share a preoccupation with establishing connections between our Earthly experience and the divine, and we place a great amount of significance upon getting the relationship right. For Christians, anyway, a key aspect of the idea of ‘right relationship’ is that it is available to all. It is good to be in good relationship with God, and all people of all nations are offered the opportunity. We humans enjoy the unique position in Creation as being God’s ‘children’. It is like a divine birthright; not something that we hoard for ourselves or dole out as we see fit, but something the comes from outside of ourselves, freely given. We don’t choose it any more than a person chooses their own parents. While it’s true that many Christians have tried to deny this birthright to others, the fact remains that we all belong to God. It follows then that an authentic Christian person would conclude, ‘so too with the aliens,’ given that – in this theoretical scenario – they must be part of God’s family also, somehow, since they possess intelligence, sentience, consciousness, and whatever other features marking the divine spirit extant within them.

Let’s get back to the missionaries, then. We’ve established that it would be likely that Christians would want to share their faith with these aliens, based upon the belief that, as fellow inheritors of God’s grace, they exist on equal footing with humanity. What might this exchange look like in practice – ethical practice, mind you? If these missionaries can do away with the historical assumption that a native populations’ spiritualities were pagan and demonic, thus requiring displacement and replacement, they might find a better way forward.

There are of course missionaries at work in the world today who follow such a path. I’ve known some. They’ve not sought to beat people over the heads with Bibles – not the ones I’ve met, anyway. These good people – many of whom I admire greatly – have adopted an approach which I think is truly in keeping with Christ’s original vision for his apostles: men and women venturing into distant and foreign lands to represent his love for his lost sheep and call them back into the fold. These missionaries reach out to forgotten and marginalized peoples; they study local languages, oftentimes ones that are neglected within their own countries; they toil and sweat alongside the community and endeavour to see it fluorish and, on occasion, even become part of it; they build trust and make friends that last for years, even lifetimes. In essence, they seek ‘the fingerprints of God’ in the people they witness to. If they look hard enough, with open and honest hearts, they find that God is at work in everyone, everywhere. It may not appear in exactly the same way as they might be used to, but the divine is present in every heart, in every culture, in all Creation – which now includes aliens.

2. Matching fingerprints

For this thought experiment to work, we must assume that the aliens these missionaries are seeking to reach have some kind of spirituality of their own – or, if not, at least a framework for which they may conceptualize spiritual or transcendent ideals. I recognize this is far from a given; I stated in an earlier piece that one of my all-time favorite science fiction works is Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris, where the alien in question is a planet-sized, sentient ocean. Lem’s chief aim in that story is to demonstrate the foolishness of assuming that alien life would be anything intelligible to humans whatsoever. Throughout the story, all attempts to establish proper communication between the ocean-creature and humanity fail miserably. There is no indication that the alien and the human share anything in common, and there is no hope that the disconnect between them might ever be breached.

But, if the aliens in our scenario were to fit this bill, the experiment would end here. So, let’s venture a little further and imagine that our aliens do possess some element of spiritual awareness and metaphysical reasoning – just like every human culture that has every existed upon Earth – as well as the capability to communicate with us regarding their beliefs. (Lem might scoff at our conveniently human-shaped newfound friends, but let him laugh – we’re just trying to have fun, aren’t we?) How then will this new generation of human missionaries seek to share their faith and convictions that Christ is our Lord and Savior in a non-judgmental or combative manner? Well, if they are truly like Christ in their humility and compassion, they will look for the fingerprints.

Let’s jump from science fiction to fantasy for just a moment. In the Chronicles of Narnia series, author and theologian C.S. Lewis imagines a liminal place called ‘The Wood’ which contains portals to many, many worlds beyond just Narnia and our own. It exists as a crossroads between the innumerable realms of creation, over which Aslan (read: Jesus) reigns sovereign. It is mentioned that Aslan is not known as ‘Aslan’ in these other worlds; indeed, he may not even appear as a lion to the denizens of these unknown places. His shape and form matter little – it is his being, his truth, that is eternal and constant. In the final book of the Narnia series – The Last Battle, the Narnian equivalent of the End Times – God/Jesus/Aslan accepts into his company a fearsome warrior who has once fought against him (and the other ‘good’ characters) as an enemy. This warrior fought zealously in the name of his own god, ostensibly different from the one recognized by the book’s protagonists. But, as Aslan later reveals, this strange god was Aslan himself in disguise. To the astonishment of all, this blaspheming enemy is shown to be a faithful friend; our human characters simply lacked the proper sense of scope when considering God/Jesus/Aslan’s divinity. The God they imagined was too small. It turned out the divine was working in many more places and in many more souls than they had ever dreamed, and they had failed to recognize its influence because of their fear, suspicion and myopia.

That was a pleasant diversion, wasn’t it? Now, back to space missionaries on the hunt for God’s fingerprints. In light of what’s been discussed thus far, it is easy to imagine these people finding inspiration in the story of the apostle Paul preaching at Mars Hill to the Gentile (non-Jew) population. Paul’s success in reaching his prospective converts lies in the winsome communication strategy he uses. Standing among the shrines to the many pagan Greek deities, he points to one empty shrine assigned to ‘the Unknown God’ and offers to describe the nature of this particular deity to his audience. Paul does not try to strip away the spirituality these people have and discard it; he speaks into it, validating it and steering it towards Christ. How is he able to do this? He recognizes that, like himself, the people to whom he’s witnessing possess the same birthright. They are God’s children just like himself, and God has been whispering to their hearts all this time. Whenever they have looked up into the sky and wondered, whenever they have hurt, whenever they have longed, whenever they have desired, whenever they have cursed, whenever they have worshipped, though it may have been in the name of a local deity or a foreign god, the spark within them that prompted that behaviour – the deeply planted kernel of faith that they hold within themselves – can be traced right back to the one true God: Paul’s God, Jesus of Nazareth.

Was Paul some kind of universalist? That’s not quite what I’m saying. Rather, I’m saying that the innate sense of spirituality that is present in all cultures, across all time (and perhaps present in all individuals as well, though that’s certainly contentious) can be attributed to God. Individuals and cultures filter, alter and shape this ‘awareness’, making sense of it in all sorts of different ways, which gives rise to the incredibly diverse range of spiritual practices and expressions that exist in our world. But God is the source of all of it, and he is drawing it all back to Himself, in His own time, to His own designs. At Mars Hill, Paul is merely redirecting people’s spiritual intuition to the original source, using the framework that they already possess for ease of access. He’s doing something along the lines of apostolic forensics: having detected the ‘fingerprints’ in the hearts of these people, he traces the evidence back to the One who touched their hearts in the first place.

Our theoretical space missionaries, I would contend, would follow this model. They would seek to understand the metaphysical frameworks used by their alien brothers and sisters, and they would look for signs of God’s handiwork within it. Where they might find it, they would point and say, “Look here: this mark you have can be ultimately attributed to the work of Christ. He is the fulfillment of these ideas you have concerning life, death, purpose, love, joy, fear, suffering and redemption. Let us tell you about him.”

And I imagine many interesting conversations would be had. Who knows – our missionaries might even begin to understand themselves in a new light, once their alien neighbors reveal their own sacred wisdoms and unique brushes with the divine. Perhaps in the exchange of our best ideas, we might all step a bit closer to the throne of God.

3. Salvation is not geocentric

We can’t help but view ourselves as the center of the universe. On our little blue planet, anything and everything that matters takes place. Stars might go supernova millions of light years away, black holes might consume entire planets in far-off galaxies, but none of it matters in the least if there is no one there to witness, to make sense of it, to ascribe meaning to it, to feel it. We can do all these things, so evidently we matter. We bring mattering into being by our very nature! We must be the most mattering of all mattering matter, I do declare.

The discovery of alien species would no doubt change this rather puffed-up view we have of ourselves. It would certainly challenge the geocentric view that exists within Christianity, which places us – our species – at the centre of the cosmic drama taking place in our universe. Christianity teaches that God sent his Son to save us – us! Jesus took the form of a man. Christ’s ultimate goal was to restore humanity to himself. How could the amphibious Blorgians from Blorgon-5 fit into this narrative?

They can’t, unless we abandon the geocentric model of salvation.

By ‘salvation’, I mean the ‘restoration of proper relationship with God’. It won’t do to get into the nitty-gritty of the nature of sin and other dense theological postulations; that discussion, while interesting, would distract from our chief aim. Let it be enough to state that, in some way, our alien neighbours would be in need of ‘restoration’ just the same as we are – according to Christians, at least. Their lives and self-expressions would in some way be incomplete or lacking harmonization with that of their Creator’s will for them. They would be rebellious children, like ourselves. We can be straightforward about what is meant by this: in the same way that we know it is wrong to lie, steal and murder, we can imagine that our alien neighbours would also have some sense of right from wrong, and that they, too, would fall short of achieving the ideals they set out for themselves. It would be hard to imagine them achieving any kind of stable civilizational model without any kind of moral structure by which to govern themselves – ah, but here’s Lem peeking his head in again, wagging his finger. Ignore him – we’ll press on.

We now have a situation where there are two divinely-sanctified species laying equal claim to the birthright of God’s ‘children’ – which is to say, those elements of Creation uniquely tasked with doing something worthwhile within the great sandbox of the cosmos – and neither of them are measuring up as being worthy to take up such a weighty mantle. What can be done? Sure, Jesus came and died on Earth to save the humans from their failures, but…what about the Blorgians?

Here is the key: Jesus’ act of salvation is cosmological, not local. It affects all Creation and all of time. Take a look at verses 15 and 16 of Chapter 1 in Colossians:

15He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; 16for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him.

We are not living in a geocentric universe. All things have been created ‘for him’. The most distant galaxy, whatever lies at the furthest edge of the universe – these things exist just as much for the purpose of declaring God’s glory as we do. The existence of our alien neighbours, while uncomfortably humbling, is exactly the same. Does this mean that Jesus died for us and the Blorgians, too, at the same time, in the same way? Again, this understanding is too narrow, and belies a geocentric bias. Whatever Jesus’ death on the cross and subsequent resurrection was, it was a cosmological event affecting everything. It was the single most significant event of its kind apart from the creation of the universe itself. Its ramifications extend out across all of time and space, as everything that has ever or will ever exist was, by this act, ‘made right’ – whatever that means.

Remember that evil existed before human beings did. We did not invent it. I suppose the Blorgians didn’t either. The Biblical account of Lucifer’s fall can be taken to say at least this much: there is a much greater battle occurring beyond the theater of our material universe, and it was been raging for much longer than we have existed. (I’d just like to note that the concept of a spiritual, extemporal battle between good and evil lasting any amount of time is inherently nonsensical, such things being unbound by the constraints of space and time, but we may examine this idea more closely in a later piece). So, at the very least, we should accept that whatever the exact nature of the spiritual conflict raging within and without ourselves, it does not begin or end with us. Greater forces are at work in the endeavour to make all that is what it ought to be.

So why should it be that we limit the scope and impact of Jesus’ sacrifice and resurrection? Can we really claim to fully understand this act so absolutely that we can establish clear boundaries over just who and what it affected, who it was for? Well, we’ve already read that it was done for all Creation, for every soul. If life on other worlds exists – and again, scientifically, it should – how can it not also be part of the great story being woven between God and his chosen peoples? It would be wrong for us to place limitations of any kind on Jesus. He was fully man, yes, but he was also fully God. In some strange and mysterious way, could there be more to the Jesus who came to Earth two thousand years ago? Could our geocentric understanding of who he was – a Galilean born under Roman occupation to a common carpenter and his wife – be clouding other possibilities, ones that elevate Christ’s glory and sovereignty to unknown heights? Could a savior figure of some type, in some way, have come to our alien neighbours to offer a path to salvation designed especially for them? Could that figure have been Jesus – in a different body, with a different name – but, like the devoted warrior of The Last Battle, committed to serving the same omnipresent source of life, truth and love? If so, we and our alien neighbours might be able to recognize these common threads between our narrative traditions and trace them back together, and in the process deepen our understanding of ourselves, our destinies and our shared relationship with the divine.

A solution to the paradox

If you’re acquainted with science fiction tropes or the search for extraterrestrial life at all, you’ve probably heard of the Fermi Paradox before. It might be one of the most widely popularized scientific quandaries. To be sure, it’s lost some of its nuance upon entering the wider cultural milieu, but the gist of it is this: where is everybody? Why can’t we seem to find evidence of life on other planets? Many potential solutions have been offered, not limited to the following:

We can’t find any aliens because we’re the first on the scene technologically, socially, developmentally, etc.

We can’t find any aliens because they’re purposely hiding from us (and no wonder).

We can’t find any aliens because they’re all dead – every intelligent species is doomed to destroy itself one way or another (again, little wonder).

But, as a final point of consideration, perhaps the true solution is at once both more straightforward and stranger than we might have guessed. Perhaps there is no ‘everybody’. Perhaps there is only us, and that’s all there ever will be. Every probe we send out is destined to vanish into the black, unheeded. Every signal we beam will never be received, heard or responded to. Every planet we visit will be dead or, at the very least, populated by microbes or some other form of unintelligent life. No one will ever answer our call because we are truly alone.

Is this a liberating thought? This solution appears clean and simple, albeit unscientific. It might appeal to a Christian person, who can rest easier knowing that we really do live in a geocentric universe – God made it all for us, and us alone. There is no need to fret over imaginary little green men and how their existence muddies our best theological constructs. By some miracle, Earth is the only planet that harbours intelligent life in this dark ocean of void. A few microbes on Europa might be a bit disconcerting, but in the end, there’s nothing to be worried about. The divine birthright is ours alone.

But I can’t help but find this solution dissatisfying, not simply because it ignores our best scientific understanding of the issue. I find it dissatisfying because, as I contemplate the vastness of our universe, I am struck by one of its most beautiful features: there is a multitude not just of things, but of different things.

God loves variety. There is no one kind of tree, one kind of mountain, one kind of breeze, one kind of bird, one kind of fish, one kind of fruit, one kind of colour, one kind of temperature, one kind of scent, one kind of sensation, one kind of emotion, one kind of gender, one kind of personality, one way to skin a cat, one kind of person, one kind of family, one kind of culture, one kind of life worth living, one kind of love. The universe in which we live is staggeringly variegated. So, when it comes to conscious, intelligent and sentient beings, why should there only be one kind?

We can’t know for certain. We should not act as if we do know. Instead, we should wonder – wonder and wander, as pneumanauts do.

This was a good read. Here’s a wild idea I’ve had for a long time. Like in the movie Thor ragnarok, “Asgard is not a place, it’s a people.” What if God’s people, Adam and Eve, were not born on earth. What if they were ‘born’ in the garden of eden not of earth but of Mars? During the fall of man, Adam and Eve found themselves on earth never to see their garden again? What if we are the ‘aliens’?

I’m not Christian, but this topic is one I’ve always found fascinating. My knowledge of the specifics might be lacking, but when approaching the topic of the crucifixion as a universal event I imagine the event on each planet/for each species as being a manifestation of an archetypal event. Christ as a universal would appear at different locations, times, and forms, as suits the specific beings to which he descends. The one saving event would be distilled into numerous events across the universe. On my side of the religious pond there are other characters and events that might be considered universal, but I reckon the framework would be similar.

One other thing that came to mind when reading this is the idea that God’s revelations to humanity were brought by human beings, and always in the language (both literal and symbolic) of the people to whom it was brought. It stands to reason that the same goes the aliens out there. It then stands to reason that even the most bizarre (from our limited perspective) models of alien intelligence would receive the fingerprints of God in a form intelligible to them—even if unintelligible to us. Makes me wish we could hurry up and make first contact, if only so that we can open up the field of xeno-comparative religious studies (or whatever it might be called)!