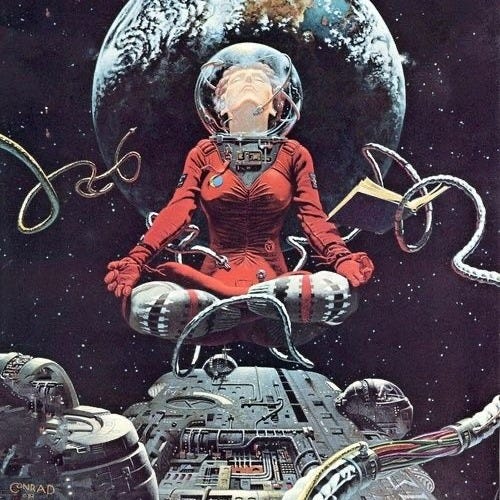

A Pneumanaut Embarks for Unknown Shores

Just where did this journey begin, and where is it headed?

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer

by Walt Whitman

Winter break, circa 2013. I was heading home from university for the holidays, travelling with my dad—an evangelical pastor. Feeling the urge for a maple dip donut and a coffee, we stepped out of the cold and into the familiar environs of a roadside Tim Horton’s (a Canadian fast-food/coffeehouse chain). I remember we talked about aliens. Real aliens, not just strangers or migrants. Extraterrestrials. Men from Mars. It wasn’t uncommon for us to talk about these sorts of things; me being an avid science fiction fan, and him being, well, my dad. We’d often fill long road trips with strange and unusual conversations on obscure theological or philosophical topics, such were our interests.

Over a pair of steaming cups of Timmies’ double-doubles, I asked him something along the lines of: “If intelligent life exists on other planets, are we supposed to go out there and convert them?”

Such was my understanding of Christians’ evangelistic calling at the time: a mandate to ‘convert’. Much has changed since then, but the idea at the core of that question has burrowed deep into my psyche. How can one understand Christ’s mission to spread the Gospel to all nations—to all our ‘neighbours’—when some of those neighbours might hail from worlds that are not Earth? Doesn’t it all begin to break down when we seriously consider that the universe may not have been created only for us? Could it have been created with others in mind, as well?

It may seem faintly ridiculous to concern oneself with the existence of extraterrestrial life and the doctrinal implications it might have for modern Christianity. After all, we hardly need to go looking on other planets to find serious wrinkles in the Biblical narrative. But it seems to me to be a perfectly reasonable question to ask, given all that we know about the universe. Statistically speaking, our galaxy should be swarming with intelligent life. Why we haven’t encountered any yet is the cause of much scientific head-scratching, but when we look at the numbers, it seems inevitable that one day we will meet our celestial neighbours. When that happens, the question of the believer’s appropriate response becomes unavoidable. I see no reason to wait until then to give it some serious thought.

It’s difficult to say why this question has gripped me so tightly, for so long. I suppose it has something to do with the answer’s potential to upend my entire worldview. I was raised in a thoroughly Christian household, and I believe, though not in the ways that I used to. My young life was shaped in every way by church culture and church life. Thankfully, the faith I’d been taught wasn’t so much dogmatic as it was pervasive. There was room to explore. Dad had worked hard to instill that in me. So I explored, taking what faith I had and venturing far into foreign places—namely, the ‘worldly’ culture lurking just outside my church-shaped bubble. I soon became enamored with many of the sub-worlds this larger world contained—those of science fiction, fantasy, horror and weird fiction—and was frequently amazed by the works of Asimov, Clarke, Le Guin, Dick, Butler, Gibson, Crighton, King, Lovecraft and countless other pulp writers. (I struggle to name a true favorite, but Stanslav Lem’s Solaris is a strong candidate.)

So it wasn’t any surprise that, when this question about alien neighbours was first articulated, I’d only left home to attend university a year or so prior. I was beginning to make sense of the world in my own unique way, but I was finding it hard to reconcile many of the things I knew to be true with the things I believed to be true. On one of my astronomy class’s nighttime observations, as an example, I beheld the entire Andromeda galaxy within the lens of my telescope. It was so much more than a blur of light—it was countless billions of individual lights, each of them a world unto themselves, streaming unfathomable distances to reach me. I was in awe, but I was also uneasy. Just like the ‘learn’d astronomer’ in Whitman’s poem, I knew that the man teaching this course could tell me everything I might want to know about that light: how it was formed, what it contained, where it was headed. The writers of books that I loved could take me there with nothing more than their words and imaginations. Where did my faith come in? Could it tell me anything that these others could not? The astonishing worlds I read about in science fiction seemed wholly divorced from the world of religion; or, if religion did indeed play a role, it was the one of the oppressive, tyrannical and socially/technologically backward enemy of progress. (It would be some time before I discovered works like Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light or Walter M. Miller Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz which offered more nuanced perspectives on the place religion might occupy in our imagined future.) How could aliens, robots, cyborgs, clones, sentient AIs, starships, singularities, dark matter, dark energy, gravitational waves and quantum mechanics all fit within the sensemaking framework laid out by Western Christianity—particularly the rather legalistic brand I’d been raised with? To synthesize these two systems of ideas cohesively—to derive a sense of purpose and a self-orientation that utilized both in equal measure—seemed impossible. There were too many incompatibilities. Science and religion stood like opposing towers, each reaching for the heavens in their own right.

I’ve given the problem much thought over the years. In my search, I haven’t shied away from thinkers whose ideas might challenge my beliefs. I remember picking up Stephen Hawking’s Brief Answers to the Big Questions from a bargain bin in a local bookstore, knowing full well that this brilliant man had ironclad reasons for not believing in the God that I did. I braced myself for some tough, paradigm-shattering scientific discourse and dove in. Even then, nothing could have prepared me for one of his most profound assertions; that it was entirely possible for the universe to give rise to itself, negating the need for a Creator. His characterization of our universe as ‘a hill and a hole adding up to nothing’ rattled my very bones. The most common justification that people of faith—including myself—offer for their beliefs threatened to crumble under the weight of this man’s genius. In essence, Hawking tells us that:

"It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going."

The laws of physics are sufficient to describe all that we see, all that is. So what is there left for faith to do? Ignore the facts and argue that he must be wrong? It seems that a binary emerges: either choose to cleave to one’s religious beliefs in the face of all contradictory evidence, or admit that great minds like those of Hawking and his ilk have demonstrated, empirically, that God is but a figment of our collective imaginations. We’re a species of storytellers, these scientists appear to be telling us, helping each other to feel less alone in a cold, impersonal cosmos.

These days, I’m less certain that the two choices are mutually exclusive. I’m hardly old and I’m hardly wise, but it does appear to be the case that the seemingly disparate worlds of science and faith may be more connected, or perhaps reflective of one another, than I was able to grasp years ago. For its part, science fiction seeks to imagine a world that may likely be, based upon the world we know today—often with frightful results. Religion, perhaps it can be said, seeks to describe the world we know and its relationship to the world beyond, the world we cannot truly ever know. But we can reach out, and sometimes we can catch glimpses. Or so we like to believe.

The simple fact is there are any number of highly intelligent, rational people who can extol the many inadequacies of a faith-based worldview, or even religion at large. They are entirely convincing and damn near unassailable. It doesn’t make much rational sense to believe in a higher power; as our technology advances and our scientific understanding of the universe deepens, the evidence appears only to be mounting to the contrary. However, there are also any number of well-educated defenders of faith with voluminous knowledge of sacred texts, apostolic writings and enlightened deliberations concerning our best understandings of the nature of God. I cannot hope to replicate their efforts. I’m not equipped to offer apologetics. What I can do, what I aim to do, is use what intellect I may have—and whatever spiritual attunement I might possess in partnership with it—and explore. Indulge in a few offbeat thought experiments. Dive deep into the webwork of consciousness, spirit, mind and cosmos, plumb the further reaches of the furthest fringes that I might reach, and attempt to chart the dark waters there. Likely any map I produce will come out more than a little wonky, but it might be worth something in the exchange. And what’s more, I feel my life depends on it. I feel a distinct urge to become a pneumanaut—an explorer of the breath, the spirit, the thing-in-me-that-is-beyond-me which sustains my sense of self and purpose. I think there may be others who feel the same.

I should set the record straight: I’m a person of faith, but I’m no science skeptic. I know we evolved from apes. I know the devil didn’t put dinosaurs here to confuse and mislead us. I know that chemical reactions in the brain shape human experience and behaviour. I know that time is relative and our perceptions of it are illusory. I know that rising from the dead is scientifically impossible, just as transmuting water into wine or restoring sight with clumps of mud are impossible. I know all that, and I do not discount it. Yet the more I learn about what science tells us about our universe, the more I come to suspect that it aligns perfectly with what we can read in the Bible and the Gospels—that is, if we are willing to consider that the truth may be much stranger and more wonderful than we could have ever possibly imagined.

But this is not a sermon, a polemic, an exhortation or a manifesto. I confess that I’m no expert. If I were to have a guiding principle, I don’t think I could do better than Socrates’ eminent paradox, ‘all I know is that I know nothing.’ On theological or scientific matters, I can’t claim to know my ups from my downs, my left from my rights or my Holy Spirits from my Higgs-Bosons. But if it’s true that at the very center of a black hole there is—well, we’re not exactly sure what there is, but that’s precisely what I’m getting at—then it doesn’t seem unreasonable to me to imagine that there’s much about ourselves and this universe we inhabit that, on a fundamental level, we don’t really understand either. And if there’s room for doubt, then there’s room to wonder. And wonder—and wander—I shall, into the ‘mystical, moist night-air’ of the unknown.

With this, I would like to welcome you to The Pneumanaut. It is a vessel, humble and leaky as it may be, designed to carry thoughts and ponderings to strange and faraway places. Whatever shores it reaches may only exist in dreams. But they are interesting dreams, and maybe when we do wake up and face the cold light of day, there will remain some fragment that suggests a way forward. I invite you, cordially, to climb aboard and see where the wind may take you.

And if it happens to blow you into a Tim Horton’s on a wintry morn, so much the better. There’s nothing better for a frosty nose and a careworn soul than a warm cup of Timmies’ best (some would say blandest) coffee.

This is a fascinating post, and I'm excited to hear more. I had the same questions about aliens and evangelism as I got into Star Trek decades ago. You're probably already aware, but C.S. Lewis engages some of these questions in his Space Trilogy. I'm not a fan of the Trilogy; I think it's poorly written. But it does raise issues such as: suppose there was an alien race that was sinless? That hadn't had their own Fall? The implications for evangelism are interesting. On another note, I get tired of Stephen Hawking's popular books where he basically "cheats" in order to get around the implications of the beginning of the universe. As someone with a philosophy degree who's also studied philosophy of science, I find Hawking sometimes ridiculous. A universe that creates itself? Absurd! There is no known physics that can explain that; he's just using his reputation to speculate on something so he doesn't have to admit there could be a Designer. He did the same thing in "A Brief History of Time." He used imaginary numbers in an effort to say there is "no boundary" for the Big Bang, so presto! No need to explain a beginning! He got into a lot of trouble from his physics colleagues, in England and elsewhere, for doing this sort of thing.

Enjoyed this intro Cam. As the "dad" in the story, one thing I would offer for your consideration - you seem to juxtapose those who are "highly intelligent, rational people who extol the inadequacies of a faith-based worldview" with those "well-educated defenders of faith with scrupulous knowledge of sacred texts" - Makes me think of people like Francis Collins (co-author of the human genome sequencing project) and John Lennox (Oxford University's Professor of Mathematics) and others like them - who are rigorous scientists and yet ardent apologists for Christian faith. There are many intelligent people who believe that science and faith actually co-exist. Looking forward to the more to come!